In Japan, with its reputation as one of the world’s safest countries, I have been exposed to sexual harassment since the age of three, forced to get used to it, and to learn to deal with it.

~Ms. Wakana Goto, Speaker at a #Me Too / #We Too rally

In 1989, Mayumi Haruno made headlines for being the first woman to challenge the legality of sexual harassment in a Japanese court. When a senior-employee at the publishing company where she was working insisted on repeatedly calling her a “serious temptress”, “adulterous”, and other inappropriate comments, she reported his misconduct to the proper authorities within the company—and was subsequently ordered to file her resignation. She vividly recalls the way her former bosses heckled her as she departed the office for the last time: “Remember to properly respect the men at your next place of employment.” Although Ms. Haruno took them to court and was eventually awarded 1.65 million yen for “illegal actions that disparaged working women,” according to her: “The situation hasn’t changed since 30 years ago.”

Japan’s Version of #Me Too

As the world focuses on the rape-trial of Harvey Weinstein in NYC, the #Me Too movement continues to pick up steam around the world. In their zeal to recreate all-things-western, Japan has established at least four similarly-themed, related movements. In addition to #Me Too, there’s also #We Too, the Flower Demo, and the curiously named #Ku Too.  The “Ku” in the #Ku Too refers to the first syllabary for “kutsu” (く), which means “shoe.” More than a few women in Japan feel that company dress-codes which require females to wear high-heels are discriminatory. So many in fact that, actress/free-lance writer, Yumi Ishikawa decided to kick-off the #Ku Too campaign. According to women I’ve spoken to, all of these movements—including #Ku Too—provide necessary platforms for victims of sexual assault / harassment to be recognized. Whether you agree or disagree with one or more of these platforms, what cannot be ignored is the fact that, in Japan, standing up for oneself—even in the name of righteousness—can easily be interpreted as “the nail who is standing out” and, of course, any such protrusion must be hammered down at all costs. That said, it is disturbing to realize this “mum’s the word” pressure even includes aggrieved parties of traumatic crimes like rape.

The “Ku” in the #Ku Too refers to the first syllabary for “kutsu” (く), which means “shoe.” More than a few women in Japan feel that company dress-codes which require females to wear high-heels are discriminatory. So many in fact that, actress/free-lance writer, Yumi Ishikawa decided to kick-off the #Ku Too campaign. According to women I’ve spoken to, all of these movements—including #Ku Too—provide necessary platforms for victims of sexual assault / harassment to be recognized. Whether you agree or disagree with one or more of these platforms, what cannot be ignored is the fact that, in Japan, standing up for oneself—even in the name of righteousness—can easily be interpreted as “the nail who is standing out” and, of course, any such protrusion must be hammered down at all costs. That said, it is disturbing to realize this “mum’s the word” pressure even includes aggrieved parties of traumatic crimes like rape.  Perhaps this is why Shiori Ito, following the Tokyo District Court’s verdict which ordered Noriyuki Yamaguchi to pay her 3.3 million yen (US$30,000), felt the need to stand outside the Municipal Court holding a banner which said: “In your face, punk! That’s right, I sued your ass!” I’m joking. In reality it read:「勝訴」 which means “winning a court case.” After filing her indictment, the backlash in Japan was so severe that Ms. Ito was forced to move to London in order to escape the daily barrage of haters, naysayers, and trolls who made it vehemently clear it was not okay, rather it was not on-code, for her to sue the former Washington bureau chief of the Tokyo Broadcasting System and biographer of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe—even if she did get raped! This explains the smug, holier-than-thou expression on Shiori’s face in the photo above. In other words, Ito-san was not missing her opportunity to serve up a little trash-talk of her own—and who could blame her?

Perhaps this is why Shiori Ito, following the Tokyo District Court’s verdict which ordered Noriyuki Yamaguchi to pay her 3.3 million yen (US$30,000), felt the need to stand outside the Municipal Court holding a banner which said: “In your face, punk! That’s right, I sued your ass!” I’m joking. In reality it read:「勝訴」 which means “winning a court case.” After filing her indictment, the backlash in Japan was so severe that Ms. Ito was forced to move to London in order to escape the daily barrage of haters, naysayers, and trolls who made it vehemently clear it was not okay, rather it was not on-code, for her to sue the former Washington bureau chief of the Tokyo Broadcasting System and biographer of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe—even if she did get raped! This explains the smug, holier-than-thou expression on Shiori’s face in the photo above. In other words, Ito-san was not missing her opportunity to serve up a little trash-talk of her own—and who could blame her?

Sexism is everywhere you go, just like gravity. It’s part of nature

~Chizuko Ueno, professor of Sociology, Tokyo University

Feminism = A Western Construct

“The world now has the impression that Japan is a sexist country lacking awareness about human rights,” said Waseda University professor Mutsuko Asakura. But is Japanese society unduly sexist? Scholars such as Ms. Sharazad Ali have made the claim that feminism, as we know it, is largely “about the white woman’s fight with her man” and, therefore, has little to do with women from more traditional cultures. A cursory look into the origin of Western civilization reveals an unveiled dislike for feminine energy. Men, in early Greece, when considering their ideal lover, were more likely to choose a young boy over a woman. Since the Greeks and Romans co-opted their spiritual pantheons from the ancient Egyptians, who had a high regard for Aset, Maat, Sekmet, and many other goddesses, they too had female deities. A few of them such as Athena, who is a replica of the Egyptian goddess, Neith, commands respect; however many western writers won’t admit she is female since she sprang forth from her father’s (Zeus) skull. Instead they have labeled her as “gender-neutral“. Rare exceptions aside, most females in Greek or Roman myths, whether humans or celestial beings, are either supporting side-kicks of males who are playing starring roles—sort of like the relationship between black and white actors in Hollywood films—or, they are the victims of rape, incest, or kidnapping. Even Hera, the “patroness and protectress of married women” is disrespected by her husband, Zeus, to such a degree that based on descriptions of her in various mythos, perhaps the most defining characteristic of the Queen of the Gods is jealousy—along with a vengeful nature against her husband’s numerous lovers and illegitimate offspring. By the 6th century, the influence of the early myths had been replaced by Christianity under the Roman emperor, Justinian. Although he declared that homosexuality was “contrary to nature” and therefore a crime punishable by death, Christianity did nothing to raise women up in society as made very plain in the first letter from St Paul to Timothy in the Bible:

Let the woman learn in silence, with all subjection. But I suffer not a woman to teach, nor to use authority over the man: but to be in silence. For Adam was first formed; then Eve.

~1 Timothy 2:11-13

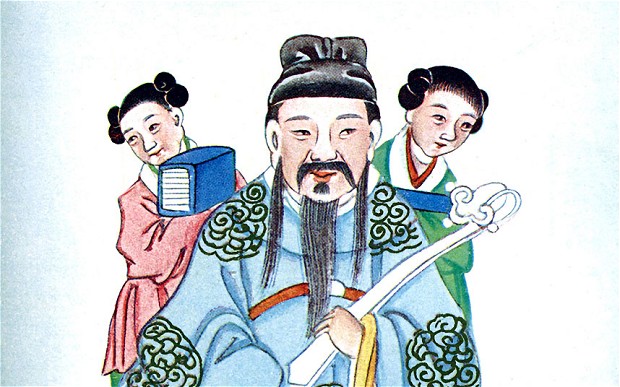

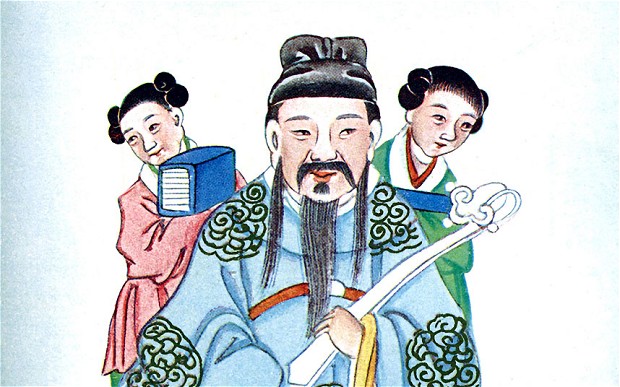

Whether God’s name is Yahweh, Jehovah, Allah, Jesus, Lord, Father, Son, (even the Holy Ghost), please note that all Judeo-Christian divinities are referred to as Him. In spite of being declared illegal, isn’t a society which features an all-male spiritual system—and no hint of female energy—still essentially homosexual in nature? Well, if you examine almost any image from this period, evidence of their peculiar preference for men is not hidden. In fact, it’s an all-male “stag party”.

Whether God’s name is Yahweh, Jehovah, Allah, Jesus, Lord, Father, Son, (even the Holy Ghost), please note that all Judeo-Christian divinities are referred to as Him. In spite of being declared illegal, isn’t a society which features an all-male spiritual system—and no hint of female energy—still essentially homosexual in nature? Well, if you examine almost any image from this period, evidence of their peculiar preference for men is not hidden. In fact, it’s an all-male “stag party”.

In contrast, more traditional spiritual systems in Africa, Asia, and even the Americas, have the divine-feminine both well-represented and well-respected. In Japan, the “national worship” derives from ancestry; and the first from that unbroken line, Amaterasu Omikami, was a woman. According to an authority on Japanese ancestor-worship, Professor Nobushige Hozumi, in spite of the absorption of Buddhism, Confucianism, and Western civilization—what he calls the “three foreign elements”—Japanese people, “whether Shintoists or Buddhists (or Christians) are all ancestor-worshippers.” In his book Great Japan; A Study of Efficiency, Alfred Stead explains prior to the introduction of Buddhism and Confucianism, “Men and women were almost equal in their social position. There was then no shadow of the barbarous idea that men were everything and women were nothing.” Women also had immense political power, with no less than nine women ascending the throne in old times. Noted for their bravery, women were outfitted with weapons just like men and fought side-by-side with their male counterparts. Perhaps the most famous female personality in Japan’s history is Empress Jingu (神功皇后), who conquered the Korean peninsula around 205 A.D. The mere fact a woman was able to lead troops into battle is sufficient proof of the female’s exalted status in society. Another point which is often overlooked (even by Japanese themselves) is women’s contribution in literature. The most famous of these writers being Murasaki Shikibu (紫 式部) with her immortal narrative, The Tale of Genji. According to Kencho Suematsu (末松 謙澄), a politician, intellectual and author during the Meiji and Taishō periods, literature depicting romance or life in the Heian period was largely left in the hands of women. This era witnessed the rise of empresses and court ladies as well as the gradual decline of emperors; so therefore, in terms of gender-equality, this would have to be considered Japan’s Golden Age.

Noted for their bravery, women were outfitted with weapons just like men and fought side-by-side with their male counterparts. Perhaps the most famous female personality in Japan’s history is Empress Jingu (神功皇后), who conquered the Korean peninsula around 205 A.D. The mere fact a woman was able to lead troops into battle is sufficient proof of the female’s exalted status in society. Another point which is often overlooked (even by Japanese themselves) is women’s contribution in literature. The most famous of these writers being Murasaki Shikibu (紫 式部) with her immortal narrative, The Tale of Genji. According to Kencho Suematsu (末松 謙澄), a politician, intellectual and author during the Meiji and Taishō periods, literature depicting romance or life in the Heian period was largely left in the hands of women. This era witnessed the rise of empresses and court ladies as well as the gradual decline of emperors; so therefore, in terms of gender-equality, this would have to be considered Japan’s Golden Age.

Fall of the Feminine

The conquest of Korea opened up the road for the introduction of Confucianism, Mencian doctrines, and Buddhism, all of which were prejudicial to the equality of the sexes

~Sidney Lewis Gulick (1860–1945), author and missionary in Japan

Three women, named Jenshinni (善信尼), Jenzoni (禅蔵尼), and Ezenni (恵善尼), were sent to India as ambassadors to investigate the tenets of Buddhism. It is ironic to think that the pioneers of a new religion which discriminates against women were not males but, in fact, were females. Dr. Gulick says: “The notions and ideals presented by Buddhism in regard to women are clear, and clearly degrading…she is essentially inferior to a man in every respect. Before she may hope to enter Nirvana she must be born again as a man.” And Confucianism was no better as indicated by the scholar, Kaibara Ekken (貝原 益軒):  “A woman must regard her husband as her lord and serve him with all the reverence and all the adoration of which she is capable…her chief duty throughout life is to obey.” In the 18th century, collections of this type of chauvinism was published in the widely read Onna Daigaku (女大学), which means The Great Learning for Women. In response, Ian Burma, in his book Behind the Mask, writes: “This seems a far cry from the world of the Sun Goddess and Izanami, where shamanesses held sway and even, like (Empress) Himiko in the third century A.D., became queens of the land…the Tokugawa government did everything to stamp out the last vestiges of matriarchy forever.”

“A woman must regard her husband as her lord and serve him with all the reverence and all the adoration of which she is capable…her chief duty throughout life is to obey.” In the 18th century, collections of this type of chauvinism was published in the widely read Onna Daigaku (女大学), which means The Great Learning for Women. In response, Ian Burma, in his book Behind the Mask, writes: “This seems a far cry from the world of the Sun Goddess and Izanami, where shamanesses held sway and even, like (Empress) Himiko in the third century A.D., became queens of the land…the Tokugawa government did everything to stamp out the last vestiges of matriarchy forever.”

Barefoot & Pregnant in the Reiwa Era?

According to a report published by the World Economic Forum, which is an annual meeting of the world’s political and economic leaders, Japan has dropped to 121st place (out of 153) in global rankings for gender-equality; this is its lowest level on record. Publicized incidents such as the recent scandal at Tokyo Medical University, where administrators altered entrance exam scores to limit the number of female candidates, or comments such as there is “no such thing [crime] as a sexual harassment charge,” uttered in 2018 by former prime-minister, Taro Aso, surely have contributed to Japan’s continuous downward spiral in the ranking. While doing research to understand Japan’s level of sexism, I was reminded of the first line in the Dickens classic, A Tale of Two Cities: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times….”  On one hand, females—especially little girls—are sexually objectified in anime, manga, and on television. On subways, specially-designated “Women-only” cars have been set aside to rescue female commuters from the all-too-common “chikan” gropings which have become synonymous with Japanese society. Though numerous reforms in education and law have resulted in the ‘New, Legal Woman’ who, just like a man, can divorce an unwanted spouse or be recognized as the ‘Head of the Household’, it can be inferred from the backlash Shiori Ito received—from both men and women—the public at large does not want women to challenge men in court…this is subversive to the Yamato Code.

On one hand, females—especially little girls—are sexually objectified in anime, manga, and on television. On subways, specially-designated “Women-only” cars have been set aside to rescue female commuters from the all-too-common “chikan” gropings which have become synonymous with Japanese society. Though numerous reforms in education and law have resulted in the ‘New, Legal Woman’ who, just like a man, can divorce an unwanted spouse or be recognized as the ‘Head of the Household’, it can be inferred from the backlash Shiori Ito received—from both men and women—the public at large does not want women to challenge men in court…this is subversive to the Yamato Code.

But on the other hand…

Unlike the targets of most unfair bias Japanese women are not minorities. Actually, they are the majority, constituting over 51% of the population. With this in mind, considering sexism is an issue which is nurtured and groomed by the entire society, is it fair to say that women, themselves, are playing a major role in their own problem? This is not to make light of anyone who is being discriminated against; however, we must consider the average woman’s level of oppression and juxtapose it with the benefits she receives. After all, it could be argued that many, if not most, women are not interested in changing the way things are.

A woman first of all influences her husband. The popular saying, ‘The husband and wife are like each other,’ speaks the same truth. Again, she is the mistress of the family, and as such her power in the family is immense…this power is surprising. What the mother likes, the child likes, and her tastes will become the tastes of the family.

~Ōkuma Shigenobu (大隈重信), former Prime Minister / founder of Waseda University

It cannot be overstated that sexual bias goes both-ways in Japan. Everyone is familiar with the hen-pecked “kaka-denka” man who is powerless in his own house because, at home, custom dictates that wives are in-charge of virtually everything, including finances. Put another way, the husband is saddled with the responsibility of bringing home the bacon; but on pay-day he hands over his entire salary to his wife. Now, who do you think came up with this arrangement? Men or women?  In his book The Future of Family and Marriage, Ritsumeikan University professor Tsutsui Jun’ya (筒井淳也) writes, “The patriarchal system was arbitrarily contrived so that men who controlled society and male members of families could maintain their privilege, even at the expense of economic productivity and growth.” Another sociologist, Minashita Kiriu, who is a professor at Kokugakuin University, teaches it was during Japan’s period of high economic growth in the Shōwa era (1926-1989) when the Japanese-style employment practices which “present a significant disadvantage to women”, such as seniority-based remuneration and lifetime employment, were created. So which is it? Is the current system the best thing since sliced bread? Or, is it an intolerant, sexist mechanism which needs to be outdated? Chizuko Ueno, who is touted as “Japan’s best known feminist”, in an interview, talked about “powerful Japanese women” who exert tremendous political pressure.

In his book The Future of Family and Marriage, Ritsumeikan University professor Tsutsui Jun’ya (筒井淳也) writes, “The patriarchal system was arbitrarily contrived so that men who controlled society and male members of families could maintain their privilege, even at the expense of economic productivity and growth.” Another sociologist, Minashita Kiriu, who is a professor at Kokugakuin University, teaches it was during Japan’s period of high economic growth in the Shōwa era (1926-1989) when the Japanese-style employment practices which “present a significant disadvantage to women”, such as seniority-based remuneration and lifetime employment, were created. So which is it? Is the current system the best thing since sliced bread? Or, is it an intolerant, sexist mechanism which needs to be outdated? Chizuko Ueno, who is touted as “Japan’s best known feminist”, in an interview, talked about “powerful Japanese women” who exert tremendous political pressure.

They are powerful even though they are not visible at the national level. Their causes may not be immediately identifiable as women’s issues or equal participation. But, for instance, if you look at anti-nuclear power activism and so forth, they actually have made a shift in local politics. Without having the support of these women, no politician can gain victory in local elections.

~Chizuko Ueno

Hmm, let’s consider this for a moment: on one hand, women have enough leverage to cause a shift in government policy on significant issues like U.S. beef and anti-nuclear legislation but, on the other hand, when it comes to having ‘sexist laws’ amended on their own behalf, they cannot seem to muster enough support. Something else worth noting is that any group which can be described as “not visible at the national level” while simultaneously being able to make “a shift” in politics, to me, sounds much more like a “hidden hand” in society than some helpless victim. Perhaps due to inherent complexities, it’s impossible for men and women to fully agree on this issue. Whatever women decide is really none of my business. However, in my humble opinion, if women were to consult with the ancestress-spirit of the past before defining what their proper role should be in 2020, all of humanity would benefit. Moreover, if they do, I feel confident they would have sense enough to aim higher than just wanting to be on-par economically with men. For this reason, perhaps I agree with the Eco-feminist critic, Aoki Yayoi (青木やよひ) when she asserts: “if all (economic independence) achieves is the right of passage of woman into existing male social structures and practices, I don’t know that we have achieved very much.”

I hope you enjoyed this edition of the Nippon Series.  Takuan Amaru is the author of Gaikokujin – The Story.

Takuan Amaru is the author of Gaikokujin – The Story.

Takuan Amaru

Takuan Amaru

In Japan, with its reputation as one of the world’s safest countries, I have been exposed to sexual harassment since the age of three, forced to get used to it, and to learn to deal with it.

~Ms. Wakana Goto, Speaker at a #Me Too / #We Too rally

In 1989, Mayumi Haruno made headlines for being the first woman to challenge the legality of sexual harassment in a Japanese court. When a senior-employee at the publishing company where she was working insisted on repeatedly calling her a “serious temptress”, “adulterous”, and other inappropriate comments, she reported his misconduct to the proper authorities within the company—and was subsequently ordered to file her resignation. She vividly recalls the way her former bosses heckled her as she departed the office for the last time: “Remember to properly respect the men at your next place of employment.” Although Ms. Haruno took them to court and was eventually awarded 1.65 million yen for “illegal actions that disparaged working women,” according to her: “The situation hasn’t changed since 30 years ago.”

Japan’s Version of #Me Too

As the world focuses on the rape-trial of Harvey Weinstein in NYC, the #Me Too movement continues to pick up steam around the world. In their zeal to recreate all-things-western, Japan has established at least four similarly-themed, related movements. In addition to #Me Too, there’s also #We Too, the Flower Demo, and the curiously named #Ku Too.  The “Ku” in the #Ku Too refers to the first syllabary for “kutsu” (く), which means “shoe.” More than a few women in Japan feel that company dress-codes which require females to wear high-heels are discriminatory. So many in fact that, actress/free-lance writer, Yumi Ishikawa decided to kick-off the #Ku Too campaign. According to women I’ve spoken to, all of these movements—including #Ku Too—provide necessary platforms for victims of sexual assault / harassment to be recognized. Whether you agree or disagree with one or more of these platforms, what cannot be ignored is the fact that, in Japan, standing up for oneself—even in the name of righteousness—can easily be interpreted as “the nail who is standing out” and, of course, any such protrusion must be hammered down at all costs. That said, it is disturbing to realize this “mum’s the word” pressure even includes aggrieved parties of traumatic crimes like rape.

The “Ku” in the #Ku Too refers to the first syllabary for “kutsu” (く), which means “shoe.” More than a few women in Japan feel that company dress-codes which require females to wear high-heels are discriminatory. So many in fact that, actress/free-lance writer, Yumi Ishikawa decided to kick-off the #Ku Too campaign. According to women I’ve spoken to, all of these movements—including #Ku Too—provide necessary platforms for victims of sexual assault / harassment to be recognized. Whether you agree or disagree with one or more of these platforms, what cannot be ignored is the fact that, in Japan, standing up for oneself—even in the name of righteousness—can easily be interpreted as “the nail who is standing out” and, of course, any such protrusion must be hammered down at all costs. That said, it is disturbing to realize this “mum’s the word” pressure even includes aggrieved parties of traumatic crimes like rape.  Perhaps this is why Shiori Ito, following the Tokyo District Court’s verdict which ordered Noriyuki Yamaguchi to pay her 3.3 million yen (US$30,000), felt the need to stand outside the Municipal Court holding a banner which said: “In your face, punk! That’s right, I sued your ass!” I’m joking. In reality it read:「勝訴」 which means “winning a court case.” After filing her indictment, the backlash in Japan was so severe that Ms. Ito was forced to move to London in order to escape the daily barrage of haters, naysayers, and trolls who made it vehemently clear it was not okay, rather it was not on-code, for her to sue the former Washington bureau chief of the Tokyo Broadcasting System and biographer of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe—even if she did get raped! This explains the smug, holier-than-thou expression on Shiori’s face in the photo above. In other words, Ito-san was not missing her opportunity to serve up a little trash-talk of her own—and who could blame her?

Perhaps this is why Shiori Ito, following the Tokyo District Court’s verdict which ordered Noriyuki Yamaguchi to pay her 3.3 million yen (US$30,000), felt the need to stand outside the Municipal Court holding a banner which said: “In your face, punk! That’s right, I sued your ass!” I’m joking. In reality it read:「勝訴」 which means “winning a court case.” After filing her indictment, the backlash in Japan was so severe that Ms. Ito was forced to move to London in order to escape the daily barrage of haters, naysayers, and trolls who made it vehemently clear it was not okay, rather it was not on-code, for her to sue the former Washington bureau chief of the Tokyo Broadcasting System and biographer of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe—even if she did get raped! This explains the smug, holier-than-thou expression on Shiori’s face in the photo above. In other words, Ito-san was not missing her opportunity to serve up a little trash-talk of her own—and who could blame her?

Sexism is everywhere you go, just like gravity. It’s part of nature

~Chizuko Ueno, professor of Sociology, Tokyo University

Feminism = A Western Construct

“The world now has the impression that Japan is a sexist country lacking awareness about human rights,” said Waseda University professor Mutsuko Asakura. But is Japanese society unduly sexist? Scholars such as Ms. Sharazad Ali have made the claim that feminism, as we know it, is largely “about the white woman’s fight with her man” and, therefore, has little to do with women from more traditional cultures. A cursory look into the origin of Western civilization reveals an unveiled dislike for feminine energy. Men, in early Greece, when considering their ideal lover, were more likely to choose a young boy over a woman. Since the Greeks and Romans co-opted their spiritual pantheons from the ancient Egyptians, who had a high regard for Aset, Maat, Sekmet, and many other goddesses, they too had female deities. A few of them such as Athena, who is a replica of the Egyptian goddess, Neith, commands respect; however many western writers won’t admit she is female since she sprang forth from her father’s (Zeus) skull. Instead they have labeled her as “gender-neutral“. Rare exceptions aside, most females in Greek or Roman myths, whether humans or celestial beings, are either supporting side-kicks of males who are playing starring roles—sort of like the relationship between black and white actors in Hollywood films—or, they are the victims of rape, incest, or kidnapping. Even Hera, the “patroness and protectress of married women” is disrespected by her husband, Zeus, to such a degree that based on descriptions of her in various mythos, perhaps the most defining characteristic of the Queen of the Gods is jealousy—along with a vengeful nature against her husband’s numerous lovers and illegitimate offspring. By the 6th century, the influence of the early myths had been replaced by Christianity under the Roman emperor, Justinian. Although he declared that homosexuality was “contrary to nature” and therefore a crime punishable by death, Christianity did nothing to raise women up in society as made very plain in the first letter from St Paul to Timothy in the Bible:

Let the woman learn in silence, with all subjection. But I suffer not a woman to teach, nor to use authority over the man: but to be in silence. For Adam was first formed; then Eve.

~1 Timothy 2:11-13

Whether God’s name is Yahweh, Jehovah, Allah, Jesus, Lord, Father, Son, (even the Holy Ghost), please note that all Judeo-Christian divinities are referred to as Him. In spite of being declared illegal, isn’t a society which features an all-male spiritual system—and no hint of female energy—still essentially homosexual in nature? Well, if you examine almost any image from this period, evidence of their peculiar preference for men is not hidden. In fact, it’s an all-male “stag party”.

Whether God’s name is Yahweh, Jehovah, Allah, Jesus, Lord, Father, Son, (even the Holy Ghost), please note that all Judeo-Christian divinities are referred to as Him. In spite of being declared illegal, isn’t a society which features an all-male spiritual system—and no hint of female energy—still essentially homosexual in nature? Well, if you examine almost any image from this period, evidence of their peculiar preference for men is not hidden. In fact, it’s an all-male “stag party”.

In contrast, more traditional spiritual systems in Africa, Asia, and even the Americas, have the divine-feminine both well-represented and well-respected. In Japan, the “national worship” derives from ancestry; and the first from that unbroken line, Amaterasu Omikami, was a woman. According to an authority on Japanese ancestor-worship, Professor Nobushige Hozumi, in spite of the absorption of Buddhism, Confucianism, and Western civilization—what he calls the “three foreign elements”—Japanese people, “whether Shintoists or Buddhists (or Christians) are all ancestor-worshippers.” In his book Great Japan; A Study of Efficiency, Alfred Stead explains prior to the introduction of Buddhism and Confucianism, “Men and women were almost equal in their social position. There was then no shadow of the barbarous idea that men were everything and women were nothing.” Women also had immense political power, with no less than nine women ascending the throne in old times. Noted for their bravery, women were outfitted with weapons just like men and fought side-by-side with their male counterparts. Perhaps the most famous female personality in Japan’s history is Empress Jingu (神功皇后), who conquered the Korean peninsula around 205 A.D. The mere fact a woman was able to lead troops into battle is sufficient proof of the female’s exalted status in society. Another point which is often overlooked (even by Japanese themselves) is women’s contribution in literature. The most famous of these writers being Murasaki Shikibu (紫 式部) with her immortal narrative, The Tale of Genji. According to Kencho Suematsu (末松 謙澄), a politician, intellectual and author during the Meiji and Taishō periods, literature depicting romance or life in the Heian period was largely left in the hands of women. This era witnessed the rise of empresses and court ladies as well as the gradual decline of emperors; so therefore, in terms of gender-equality, this would have to be considered Japan’s Golden Age.

Noted for their bravery, women were outfitted with weapons just like men and fought side-by-side with their male counterparts. Perhaps the most famous female personality in Japan’s history is Empress Jingu (神功皇后), who conquered the Korean peninsula around 205 A.D. The mere fact a woman was able to lead troops into battle is sufficient proof of the female’s exalted status in society. Another point which is often overlooked (even by Japanese themselves) is women’s contribution in literature. The most famous of these writers being Murasaki Shikibu (紫 式部) with her immortal narrative, The Tale of Genji. According to Kencho Suematsu (末松 謙澄), a politician, intellectual and author during the Meiji and Taishō periods, literature depicting romance or life in the Heian period was largely left in the hands of women. This era witnessed the rise of empresses and court ladies as well as the gradual decline of emperors; so therefore, in terms of gender-equality, this would have to be considered Japan’s Golden Age.

Fall of the Feminine

The conquest of Korea opened up the road for the introduction of Confucianism, Mencian doctrines, and Buddhism, all of which were prejudicial to the equality of the sexes

~Sidney Lewis Gulick (1860–1945), author and missionary in Japan

Three women, named Jenshinni (善信尼), Jenzoni (禅蔵尼), and Ezenni (恵善尼), were sent to India as ambassadors to investigate the tenets of Buddhism. It is ironic to think that the pioneers of a new religion which discriminates against women were not males but, in fact, were females. Dr. Gulick says: “The notions and ideals presented by Buddhism in regard to women are clear, and clearly degrading…she is essentially inferior to a man in every respect. Before she may hope to enter Nirvana she must be born again as a man.” And Confucianism was no better as indicated by the scholar, Kaibara Ekken (貝原 益軒):  “A woman must regard her husband as her lord and serve him with all the reverence and all the adoration of which she is capable…her chief duty throughout life is to obey.” In the 18th century, collections of this type of chauvinism was published in the widely read Onna Daigaku (女大学), which means The Great Learning for Women. In response, Ian Burma, in his book Behind the Mask, writes: “This seems a far cry from the world of the Sun Goddess and Izanami, where shamanesses held sway and even, like (Empress) Himiko in the third century A.D., became queens of the land…the Tokugawa government did everything to stamp out the last vestiges of matriarchy forever.”

“A woman must regard her husband as her lord and serve him with all the reverence and all the adoration of which she is capable…her chief duty throughout life is to obey.” In the 18th century, collections of this type of chauvinism was published in the widely read Onna Daigaku (女大学), which means The Great Learning for Women. In response, Ian Burma, in his book Behind the Mask, writes: “This seems a far cry from the world of the Sun Goddess and Izanami, where shamanesses held sway and even, like (Empress) Himiko in the third century A.D., became queens of the land…the Tokugawa government did everything to stamp out the last vestiges of matriarchy forever.”

Barefoot & Pregnant in the Reiwa Era?

According to a report published by the World Economic Forum, which is an annual meeting of the world’s political and economic leaders, Japan has dropped to 121st place (out of 153) in global rankings for gender-equality; this is its lowest level on record. Publicized incidents such as the recent scandal at Tokyo Medical University, where administrators altered entrance exam scores to limit the number of female candidates, or comments such as there is “no such thing [crime] as a sexual harassment charge,” uttered in 2018 by former prime-minister, Taro Aso, surely have contributed to Japan’s continuous downward spiral in the ranking. While doing research to understand Japan’s level of sexism, I was reminded of the first line in the Dickens classic, A Tale of Two Cities: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times….”  On one hand, females—especially little girls—are sexually objectified in anime, manga, and on television. On subways, specially-designated “Women-only” cars have been set aside to rescue female commuters from the all-too-common “chikan” gropings which have become synonymous with Japanese society. Though numerous reforms in education and law have resulted in the ‘New, Legal Woman’ who, just like a man, can divorce an unwanted spouse or be recognized as the ‘Head of the Household’, it can be inferred from the backlash Shiori Ito received—from both men and women—the public at large does not want women to challenge men in court…this is subversive to the Yamato Code.

On one hand, females—especially little girls—are sexually objectified in anime, manga, and on television. On subways, specially-designated “Women-only” cars have been set aside to rescue female commuters from the all-too-common “chikan” gropings which have become synonymous with Japanese society. Though numerous reforms in education and law have resulted in the ‘New, Legal Woman’ who, just like a man, can divorce an unwanted spouse or be recognized as the ‘Head of the Household’, it can be inferred from the backlash Shiori Ito received—from both men and women—the public at large does not want women to challenge men in court…this is subversive to the Yamato Code.

But on the other hand…

Unlike the targets of most unfair bias Japanese women are not minorities. Actually, they are the majority, constituting over 51% of the population. With this in mind, considering sexism is an issue which is nurtured and groomed by the entire society, is it fair to say that women, themselves, are playing a major role in their own problem? This is not to make light of anyone who is being discriminated against; however, we must consider the average woman’s level of oppression and juxtapose it with the benefits she receives. After all, it could be argued that many, if not most, women are not interested in changing the way things are.

A woman first of all influences her husband. The popular saying, ‘The husband and wife are like each other,’ speaks the same truth. Again, she is the mistress of the family, and as such her power in the family is immense…this power is surprising. What the mother likes, the child likes, and her tastes will become the tastes of the family.

~Ōkuma Shigenobu (大隈重信), former Prime Minister / founder of Waseda University

It cannot be overstated that sexual bias goes both-ways in Japan. Everyone is familiar with the hen-pecked “kaka-denka” man who is powerless in his own house because, at home, custom dictates that wives are in-charge of virtually everything, including finances. Put another way, the husband is saddled with the responsibility of bringing home the bacon; but on pay-day he hands over his entire salary to his wife. Now, who do you think came up with this arrangement? Men or women?  In his book The Future of Family and Marriage, Ritsumeikan University professor Tsutsui Jun’ya (筒井淳也) writes, “The patriarchal system was arbitrarily contrived so that men who controlled society and male members of families could maintain their privilege, even at the expense of economic productivity and growth.” Another sociologist, Minashita Kiriu, who is a professor at Kokugakuin University, teaches it was during Japan’s period of high economic growth in the Shōwa era (1926-1989) when the Japanese-style employment practices which “present a significant disadvantage to women”, such as seniority-based remuneration and lifetime employment, were created. So which is it? Is the current system the best thing since sliced bread? Or, is it an intolerant, sexist mechanism which needs to be outdated? Chizuko Ueno, who is touted as “Japan’s best known feminist”, in an interview, talked about “powerful Japanese women” who exert tremendous political pressure.

In his book The Future of Family and Marriage, Ritsumeikan University professor Tsutsui Jun’ya (筒井淳也) writes, “The patriarchal system was arbitrarily contrived so that men who controlled society and male members of families could maintain their privilege, even at the expense of economic productivity and growth.” Another sociologist, Minashita Kiriu, who is a professor at Kokugakuin University, teaches it was during Japan’s period of high economic growth in the Shōwa era (1926-1989) when the Japanese-style employment practices which “present a significant disadvantage to women”, such as seniority-based remuneration and lifetime employment, were created. So which is it? Is the current system the best thing since sliced bread? Or, is it an intolerant, sexist mechanism which needs to be outdated? Chizuko Ueno, who is touted as “Japan’s best known feminist”, in an interview, talked about “powerful Japanese women” who exert tremendous political pressure.

They are powerful even though they are not visible at the national level. Their causes may not be immediately identifiable as women’s issues or equal participation. But, for instance, if you look at anti-nuclear power activism and so forth, they actually have made a shift in local politics. Without having the support of these women, no politician can gain victory in local elections.

~Chizuko Ueno

Hmm, let’s consider this for a moment: on one hand, women have enough leverage to cause a shift in government policy on significant issues like U.S. beef and anti-nuclear legislation but, on the other hand, when it comes to having ‘sexist laws’ amended on their own behalf, they cannot seem to muster enough support. Something else worth noting is that any group which can be described as “not visible at the national level” while simultaneously being able to make “a shift” in politics, to me, sounds much more like a “hidden hand” in society than some helpless victim. Perhaps due to inherent complexities, it’s impossible for men and women to fully agree on this issue. Whatever women decide is really none of my business. However, in my humble opinion, if women were to consult with the ancestress-spirit of the past before defining what their proper role should be in 2020, all of humanity would benefit. Moreover, if they do, I feel confident they would have sense enough to aim higher than just wanting to be on-par economically with men. For this reason, perhaps I agree with the Eco-feminist critic, Aoki Yayoi (青木やよひ) when she asserts: “if all (economic independence) achieves is the right of passage of woman into existing male social structures and practices, I don’t know that we have achieved very much.”

I hope you enjoyed this edition of the Nippon Series.  Takuan Amaru is the author of Gaikokujin – The Story.

Takuan Amaru is the author of Gaikokujin – The Story.