From 2002-2008, I was a teacher at a private high school in Kyoto, Japan. One winter, I had the pleasure of traveling to Brazil to celebrate Carnaval. Upon my return, I was excited to recount my experience because I knew the teachers and students assumed I had went to Rio de Janeiro. However my friends and I were interested in Afro-Brazilian culture; therefore we decided to go to Bahia. Located along the northeast seaboard nearest to the west coast of the African continent, Bahia became the first established port in the Americas for the importation of goods from Africa which, of course, included kidnapped Africans.

Upon my return, I was excited to recount my experience because I knew the teachers and students assumed I had went to Rio de Janeiro. However my friends and I were interested in Afro-Brazilian culture; therefore we decided to go to Bahia. Located along the northeast seaboard nearest to the west coast of the African continent, Bahia became the first established port in the Americas for the importation of goods from Africa which, of course, included kidnapped Africans.

Loaded down with all types of souvenirs and memorabilia, I remember stumbling into the classroom ten minutes early to set-up the slide-show. Nevertheless, all this effort turned out to be a waste of time as no one was the least bit interested in learning about the African nuances embedded in Brazilian culture. Instead, it seemed, the students only wanted to discuss the dangers of life in Brazil. “Weren’t you afraid?” one boy asked. “Did you see anyone get killed?” asked another girl next to him.

Feeling disappointed that no one wanted to hear about my trip, I decided to disagree with them, at any cost. “Afraid?” I retorted in feigned surprise. “Afraid of what? If you think about it,” I said, looking at the boy. “Brazil’s not nearly as dangerous as Japan.” Again, I said this just to be disagreeable.  I only wanted to rattle the students a little about their beloved country before telling them the truth; which was that we did see our share of violence—mostly from the police patrolling the festivities. Walking in single-file with tonfas strapped to their belts, these stormtroopers would beat anyone who they deemed looked suspect. For this reason, as you can probably imagine, my anxiety level skyrocketed once I heard a voice which I knew belonged to the vice-principal.

I only wanted to rattle the students a little about their beloved country before telling them the truth; which was that we did see our share of violence—mostly from the police patrolling the festivities. Walking in single-file with tonfas strapped to their belts, these stormtroopers would beat anyone who they deemed looked suspect. For this reason, as you can probably imagine, my anxiety level skyrocketed once I heard a voice which I knew belonged to the vice-principal.

“Amaru-sensei, he uttered in response to my comparison between Brazil and Japan, “what do you mean? Can you give us an example?”

Hastily turning my head toward the sound of his voice, only then did I realize in addition to Kyoto-sensei, three other teachers had entered the room. Although I recalled inviting the entire staff to observe my lesson about Brazil in the chorei (morning meeting), since I was just practicing tatamae, I never expected anyone to actually show up. Feeling more than a little nervous and put on the spot, I was just about to concede that I was joking when a thought suddenly took hold of my mind. “Hiki-komori,” I blurted out without thinking.

This was met with dead-silence. From my vantage point, it appeared the students and staff were taking their cues on how to respond from the vice-principal’s reaction. For this reason, I exhaled a sigh of relief when the vice-principal started nodding his head in agreement. Seeing this emboldened me to speak further as the murmurs of thirty-plus students circulated around the room. “And of course, we can add jisatsu (suicide), karoshi (death from overwork), and just general ijime (bullying) into the mix. All of these are “special dangers” which are pretty much unique to Japan. So yeah, there’s some danger when traveling to (so-called) developing countries; however, since it’s ‘obvious danger’ that everyone knows about,” saying this, I began tapping an index-finger against my right temple, ” by using your common-sense it can be eliminated.

“What do you mean?” asked the same girl from the first row.

“Yumiko-san, there are many methods designed to stop criminals from entering your space, right?” I paused to encourage Yumiko to think on her own. “Burglar alarms, guard-dogs, security cameras, or just simply calling for help. This type of danger—which is basically what you face in Brazil—comes from criminals who are outside but,” pausing here I looked around the room, “the danger in Japan is different—it’s much more lethal because the criminal attacking you is inside so no one can help you, not even the police.”

“Inside what?” inquired the boy next to her, Masafumi, as if it was his turn to speak.

Before I could respond, Kyoto-sensei interjected on my behalf. “Inside of you, Masafumi-kun.” While saying this, he walked toward the front of the room. “Amaru-sensei is saying that here, in Japan, we have shown the tendency of becoming our own worst enemy…sometimes even becoming our own murderer.” Now standing next to me, he turned to face the students. “And he is absolutely correct.” Flabbergasted that Kyoto-sensei would agree with me on such a controversial issue, I was almost at a loss for words to answer his next question. “Amaru-sensei,” he began, “it is said that Japan is among the safest countries in the world. What is your opinion?”

My natural impulse was to agree. After all, compared to any country I’d lived in, Japan is the cleanest, most harmonious, and the most crime-free. Nevertheless, something about this blanket statement did not sit right with me and I knew what it was. Put simply Japan isn’t safe!  In fact, it’s fraught with countless dangers which are unique to the tiny, island-nation. While many believe that external danger in the form of thieves, police brutality, corruption, gang violence, muggings, etc. pose the greatest threat, I would argue that the “pressure-cooker” internal variety, which gradually drives people insane and encourages the victim to abuse him/herself is much more menacing. Again use your common sense, we’re talking about being overloaded with stress; and not only is stress legal, it’s actually sanctioned by society.

In fact, it’s fraught with countless dangers which are unique to the tiny, island-nation. While many believe that external danger in the form of thieves, police brutality, corruption, gang violence, muggings, etc. pose the greatest threat, I would argue that the “pressure-cooker” internal variety, which gradually drives people insane and encourages the victim to abuse him/herself is much more menacing. Again use your common sense, we’re talking about being overloaded with stress; and not only is stress legal, it’s actually sanctioned by society.

Modern Japan

The financial assistance provided to Japan by the U.S. following World War II led to the Bubble Economy of the 1980s. As Japanese society modernized from a rural, agricultural society into the era of technology, one of the consequences was forcing men away from their homes to work long hours as a salaryman. Not only did this severely limit interaction with their children, but in addition, according to Dr. Henry Grub of Maryland University, these white-collar positions “took away the skills which gave men any prestige in their children’s eyes.” The fact this occurred simultaneously with a sharp increase in single-child families cannot be overstated. In essence, women have been left at home to cope with a child all by themselves; and, in too many cases, this has led to an estranged, isolated situation for the mother and child—especially when the child is a boy. Having no siblings to practice social skills, plus the lack of a male role-model in the home (to enforce rules), has led to various societal phenomena.

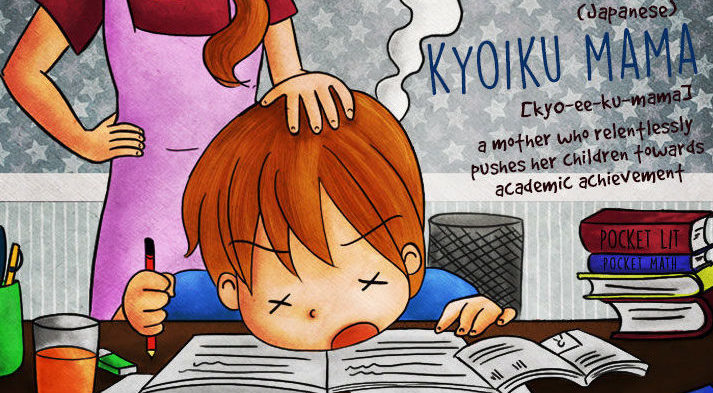

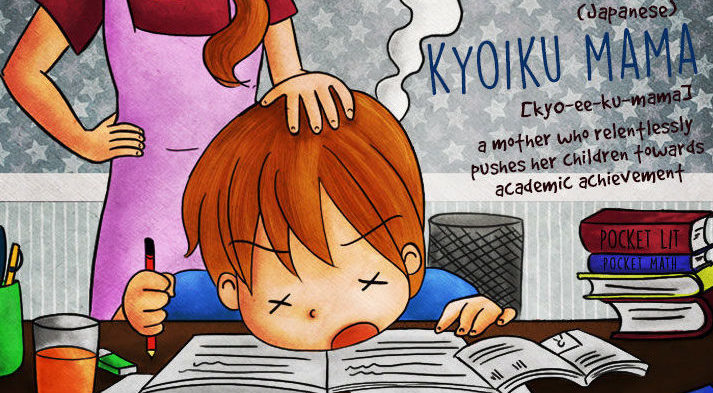

Kyōiku mama (教育ママ)

This Japanese pejorative term, which literally translates as “education mother,” is a stereotyped figure in modern Japanese society. This strong-willed mother is portrayed as a woman who relentlessly drives her child to study—to the detriment of the child’s social, physical, and emotional development. Similar to other cultures’ stereotypes of self-sacrificing, strict mothers who coerce their children to success such as the Chinese Tiger Mother, or the American Stage Mother, the Kyoiku mama is feared and resented by her children and has been blamed (by the media) for medical issues including bronchial asthma, stammering, poor appetite, and proneness to bone fractures, not to mention mental-health issues such as school phobias, youth suicides, and even the advent of perhaps the greatest social menace of the 21st Century: the Hikikomori.

Similar to other cultures’ stereotypes of self-sacrificing, strict mothers who coerce their children to success such as the Chinese Tiger Mother, or the American Stage Mother, the Kyoiku mama is feared and resented by her children and has been blamed (by the media) for medical issues including bronchial asthma, stammering, poor appetite, and proneness to bone fractures, not to mention mental-health issues such as school phobias, youth suicides, and even the advent of perhaps the greatest social menace of the 21st Century: the Hikikomori.

(In Japan) A person’s value is contingent upon their ability to conform to the norms of society. However, hikikomori are unable to conform; therefore they feel completely useless

~ Teppei Sekimizu

Hikikomori (引きこもり)

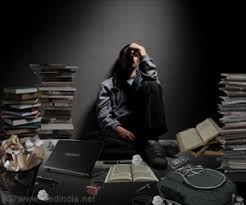

Literally translating as “pulling inward, being confined,” this acute mental condition results in a complete withdrawal away from people. These societal recluses, which include both Japanese youth as well as the middle-aged, have been estimated in excess of a million people. Until recently, although hikikomori may have been embarrassments to their families, they were pretty much viewed as harmless. Nonetheless, in the spring of 2019, in the wake of some tragic murders which occurred in the Tokyo area, public opinion has been changing concerning this mental-health condition. Hideaki Kumazawa, a 76-year-old retired bureaucrat from the Agriculture Ministry, stabbed his 44-year-old son, Eiichiro, to death. Mr. Kumazawa claimed it was his duty to kill his son in order to prevent another violent outbreak such as the one which occurred on May 28, in Kawasaki City. On that fateful morning, a 57-year-old man—who was alleged to be hikikomori—stabbed 17 people, resulting in 2 deaths before also killing himself. Since then, hikikomori in their 40s and 50s (with parents in their 70s and 80s), have been a target for media attention. Dr. Carla Ricci, an anthropologist and researcher at the Department of Clinical Psychology at the University of Tokyo, searched for hikikomori in Italy and discovered a case in the southern part of the country. Since Italians are not known for having a stressful work society, she searched for something else the two countries shared in common. Dr. Ricci claims that, similar to Japan, Italian households tend to be matriarchal. Could the pressure exacted by overbearing Japanese mothers be to blame for millions of socially inept offspring who may later develop violent behavior?

Hideaki Kumazawa, a 76-year-old retired bureaucrat from the Agriculture Ministry, stabbed his 44-year-old son, Eiichiro, to death. Mr. Kumazawa claimed it was his duty to kill his son in order to prevent another violent outbreak such as the one which occurred on May 28, in Kawasaki City. On that fateful morning, a 57-year-old man—who was alleged to be hikikomori—stabbed 17 people, resulting in 2 deaths before also killing himself. Since then, hikikomori in their 40s and 50s (with parents in their 70s and 80s), have been a target for media attention. Dr. Carla Ricci, an anthropologist and researcher at the Department of Clinical Psychology at the University of Tokyo, searched for hikikomori in Italy and discovered a case in the southern part of the country. Since Italians are not known for having a stressful work society, she searched for something else the two countries shared in common. Dr. Ricci claims that, similar to Japan, Italian households tend to be matriarchal. Could the pressure exacted by overbearing Japanese mothers be to blame for millions of socially inept offspring who may later develop violent behavior?

Mind Playing Tricks

Many of us have no problem going on vacation (or living) in urban areas with high crime rates like NYC, London, or Paris as long as we stay in buildings equipped with gates, alarms, and security-cameras. Once inside our locked doors we feel pretty safe. However, what if the stress of this world became so great—so unbearable—that you started hearing voices telling you to kill yourself? How could you possibly hope to protect yourself from yourself?

I’ve had the pleasure to teach and coach sports in more than a few schools and universities throughout Japan. Overall, my teaching experience has been very rewarding; however in every school where I worked, at some point, there was talk about a student (or teacher) who was contemplating suicide. Many people know that Japan has a special relationship with suicide, but most are unaware to what extent. Let’s put it like this: if there are less than 30,000 suicides committed annually, Japan considers this a good year. 30,000 deaths! In 2014, it was reported that, on average, 70 people committed suicide every day! Please understand that ritualized death has been historically woven into the fabric of Japanese society, therefore there are various categories and some of them are considered honorable.

Death Culture

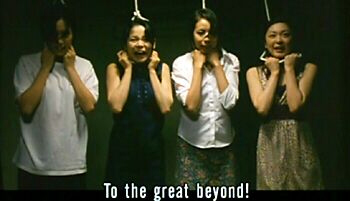

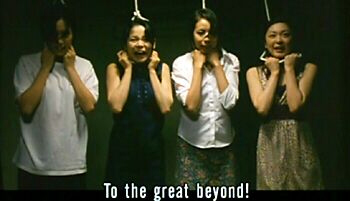

According to the late author/actor, Yukio Mishima, who disemboweled himself in what is probably the most publicized suicide in Japanese history, seppuku (切腹) differs from “the western concept of suicide.” Originally reserved for samurai families, eventually it became a method for people of any class to restore honor for themselves or their family. Most people are aware of the Kamikaze pilots during World War II who became renowned for crashing their planes into the enemy ships. In addition to seppuku, there are several death-ritual categories not commonly found outside of Japan such as shidoshi (指導死), which is students who kill themselves as a result of teachers being too strict; or karoshi (過労死), which is death from overwork. Another popular category is Shinjū (心中), which are suicide pacts formed among individuals. Nowadays, the victims are usually strangers but traditionally, especially in the bunraku puppet theaters of the 17th century, this final-act was undertaken by two people bound by love—typically lovers or parent and child. The more contemporary version, which may include more than two people, has become so popular it has been dubbed “Internet Group Suicide.”

These people share in common a longing to end the suffering called life; and therefore, they vow to end theirs together at the same time, using the same method. The ever-increasing popularity of these pacts have resulted in the rise of famous “suicide areas” where police constantly patrol in an attempt to catch victims before they can fulfill their grim objectives. A forest at the base of Mount Fuji, called Aokigahara, reported 247 suicide attempts in 2010. Another such site in Fukui Prefecture, Tōjinbō, is a series of cliffs along the Sea of Japan. Legend claims that a Buddhist priest named Tōjinbō was disliked by the townspeople so much they threw him off the 70-foot-high cliffs and his spirit still haunts the area. Yukio Shige, a retired police officer, took it upon himself to patrol the cliffs, and in 2015 reported that his efforts saved over 500 lives. Railroad tracks have become such a common place for suicide that in an attempt to decrease incidents, Japanese railroad companies have installed chest-high track barriers as well as blue-tinted lights which are intended to calm people’s moods. As a further deterrent, there is a hefty fine to be paid by the surviving family members of anyone who commits suicide by laying down on the tracks for “the disruption of service.”

These people share in common a longing to end the suffering called life; and therefore, they vow to end theirs together at the same time, using the same method. The ever-increasing popularity of these pacts have resulted in the rise of famous “suicide areas” where police constantly patrol in an attempt to catch victims before they can fulfill their grim objectives. A forest at the base of Mount Fuji, called Aokigahara, reported 247 suicide attempts in 2010. Another such site in Fukui Prefecture, Tōjinbō, is a series of cliffs along the Sea of Japan. Legend claims that a Buddhist priest named Tōjinbō was disliked by the townspeople so much they threw him off the 70-foot-high cliffs and his spirit still haunts the area. Yukio Shige, a retired police officer, took it upon himself to patrol the cliffs, and in 2015 reported that his efforts saved over 500 lives. Railroad tracks have become such a common place for suicide that in an attempt to decrease incidents, Japanese railroad companies have installed chest-high track barriers as well as blue-tinted lights which are intended to calm people’s moods. As a further deterrent, there is a hefty fine to be paid by the surviving family members of anyone who commits suicide by laying down on the tracks for “the disruption of service.”

Conclusion

As I collected information for this article, I checked out several suicide-prevention websites. Each of them preached the same window-dressing remedies of education, investing in research, and communication; but nothing addressed the huge, nasty elephant in the room. No one wants to assign blame to, nor shoulder any responsibility for (their participation in), a sick, biased society…a death culture. Acute social-withdrawal is not temperamental shyness but, rather, it’s a marked change in which an individual used to be engaged with family and friends and, due to some form of trauma, she/he suddenly decides to withdraw away from people. Dr. Thomas Joiner, author of Why People Die, calls this “an inward gaze of bemused resignation and resolution.”

Understanding there are virtually no ghettos or slum areas in Tokyo or Osaka, it’s easy to compare Japan’s Hikikomori crisis with the homeless situation in most western countries; both have turned away from society and both are seen as pariahs. What could be so traumatizing about the society in a (so-called) developed country that it results in millions of people throwing in the towel and giving up?

Hmm, I think that brings us back to the stinky elephant in the room.

Note: This is only one of topics that will be covered (in more detail) in the upcoming book: Modern Japan—decoded!

Takuan Amaru is the author of the trilogy, Gaikokujin – The Story.

Reference

Thomas Joiner, Why People Die by Suicide (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2006).

Takuan Amaru

From 2002-2008, I was a teacher at a private high school in Kyoto, Japan. One winter, I had the pleasure of traveling to Brazil to celebrate Carnaval. Upon my return, I was excited to recount my experience because I knew the teachers and students assumed I had went to Rio de Janeiro. However my friends and I were interested in Afro-Brazilian culture; therefore we decided to go to Bahia. Located along the northeast seaboard nearest to the west coast of the African continent, Bahia became the first established port in the Americas for the importation of goods from Africa which, of course, included kidnapped Africans.

Upon my return, I was excited to recount my experience because I knew the teachers and students assumed I had went to Rio de Janeiro. However my friends and I were interested in Afro-Brazilian culture; therefore we decided to go to Bahia. Located along the northeast seaboard nearest to the west coast of the African continent, Bahia became the first established port in the Americas for the importation of goods from Africa which, of course, included kidnapped Africans.

Loaded down with all types of souvenirs and memorabilia, I remember stumbling into the classroom ten minutes early to set-up the slide-show. Nevertheless, all this effort turned out to be a waste of time as no one was the least bit interested in learning about the African nuances embedded in Brazilian culture. Instead, it seemed, the students only wanted to discuss the dangers of life in Brazil. “Weren’t you afraid?” one boy asked. “Did you see anyone get killed?” asked another girl next to him.

Feeling disappointed that no one wanted to hear about my trip, I decided to disagree with them, at any cost. “Afraid?” I retorted in feigned surprise. “Afraid of what? If you think about it,” I said, looking at the boy. “Brazil’s not nearly as dangerous as Japan.” Again, I said this just to be disagreeable.  I only wanted to rattle the students a little about their beloved country before telling them the truth; which was that we did see our share of violence—mostly from the police patrolling the festivities. Walking in single-file with tonfas strapped to their belts, these stormtroopers would beat anyone who they deemed looked suspect. For this reason, as you can probably imagine, my anxiety level skyrocketed once I heard a voice which I knew belonged to the vice-principal.

I only wanted to rattle the students a little about their beloved country before telling them the truth; which was that we did see our share of violence—mostly from the police patrolling the festivities. Walking in single-file with tonfas strapped to their belts, these stormtroopers would beat anyone who they deemed looked suspect. For this reason, as you can probably imagine, my anxiety level skyrocketed once I heard a voice which I knew belonged to the vice-principal.

“Amaru-sensei, he uttered in response to my comparison between Brazil and Japan, “what do you mean? Can you give us an example?”

Hastily turning my head toward the sound of his voice, only then did I realize in addition to Kyoto-sensei, three other teachers had entered the room. Although I recalled inviting the entire staff to observe my lesson about Brazil in the chorei (morning meeting), since I was just practicing tatamae, I never expected anyone to actually show up. Feeling more than a little nervous and put on the spot, I was just about to concede that I was joking when a thought suddenly took hold of my mind. “Hiki-komori,” I blurted out without thinking.

This was met with dead-silence. From my vantage point, it appeared the students and staff were taking their cues on how to respond from the vice-principal’s reaction. For this reason, I exhaled a sigh of relief when the vice-principal started nodding his head in agreement. Seeing this emboldened me to speak further as the murmurs of thirty-plus students circulated around the room. “And of course, we can add jisatsu (suicide), karoshi (death from overwork), and just general ijime (bullying) into the mix. All of these are “special dangers” which are pretty much unique to Japan. So yeah, there’s some danger when traveling to (so-called) developing countries; however, since it’s ‘obvious danger’ that everyone knows about,” saying this, I began tapping an index-finger against my right temple, ” by using your common-sense it can be eliminated.

“What do you mean?” asked the same girl from the first row.

“Yumiko-san, there are many methods designed to stop criminals from entering your space, right?” I paused to encourage Yumiko to think on her own. “Burglar alarms, guard-dogs, security cameras, or just simply calling for help. This type of danger—which is basically what you face in Brazil—comes from criminals who are outside but,” pausing here I looked around the room, “the danger in Japan is different—it’s much more lethal because the criminal attacking you is inside so no one can help you, not even the police.”

“Inside what?” inquired the boy next to her, Masafumi, as if it was his turn to speak.

Before I could respond, Kyoto-sensei interjected on my behalf. “Inside of you, Masafumi-kun.” While saying this, he walked toward the front of the room. “Amaru-sensei is saying that here, in Japan, we have shown the tendency of becoming our own worst enemy…sometimes even becoming our own murderer.” Now standing next to me, he turned to face the students. “And he is absolutely correct.” Flabbergasted that Kyoto-sensei would agree with me on such a controversial issue, I was almost at a loss for words to answer his next question. “Amaru-sensei,” he began, “it is said that Japan is among the safest countries in the world. What is your opinion?”

My natural impulse was to agree. After all, compared to any country I’d lived in, Japan is the cleanest, most harmonious, and the most crime-free. Nevertheless, something about this blanket statement did not sit right with me and I knew what it was. Put simply Japan isn’t safe!  In fact, it’s fraught with countless dangers which are unique to the tiny, island-nation. While many believe that external danger in the form of thieves, police brutality, corruption, gang violence, muggings, etc. pose the greatest threat, I would argue that the “pressure-cooker” internal variety, which gradually drives people insane and encourages the victim to abuse him/herself is much more menacing. Again use your common sense, we’re talking about being overloaded with stress; and not only is stress legal, it’s actually sanctioned by society.

In fact, it’s fraught with countless dangers which are unique to the tiny, island-nation. While many believe that external danger in the form of thieves, police brutality, corruption, gang violence, muggings, etc. pose the greatest threat, I would argue that the “pressure-cooker” internal variety, which gradually drives people insane and encourages the victim to abuse him/herself is much more menacing. Again use your common sense, we’re talking about being overloaded with stress; and not only is stress legal, it’s actually sanctioned by society.

Modern Japan

The financial assistance provided to Japan by the U.S. following World War II led to the Bubble Economy of the 1980s. As Japanese society modernized from a rural, agricultural society into the era of technology, one of the consequences was forcing men away from their homes to work long hours as a salaryman. Not only did this severely limit interaction with their children, but in addition, according to Dr. Henry Grub of Maryland University, these white-collar positions “took away the skills which gave men any prestige in their children’s eyes.” The fact this occurred simultaneously with a sharp increase in single-child families cannot be overstated. In essence, women have been left at home to cope with a child all by themselves; and, in too many cases, this has led to an estranged, isolated situation for the mother and child—especially when the child is a boy. Having no siblings to practice social skills, plus the lack of a male role-model in the home (to enforce rules), has led to various societal phenomena.

Kyōiku mama (教育ママ)

This Japanese pejorative term, which literally translates as “education mother,” is a stereotyped figure in modern Japanese society. This strong-willed mother is portrayed as a woman who relentlessly drives her child to study—to the detriment of the child’s social, physical, and emotional development. Similar to other cultures’ stereotypes of self-sacrificing, strict mothers who coerce their children to success such as the Chinese Tiger Mother, or the American Stage Mother, the Kyoiku mama is feared and resented by her children and has been blamed (by the media) for medical issues including bronchial asthma, stammering, poor appetite, and proneness to bone fractures, not to mention mental-health issues such as school phobias, youth suicides, and even the advent of perhaps the greatest social menace of the 21st Century: the Hikikomori.

Similar to other cultures’ stereotypes of self-sacrificing, strict mothers who coerce their children to success such as the Chinese Tiger Mother, or the American Stage Mother, the Kyoiku mama is feared and resented by her children and has been blamed (by the media) for medical issues including bronchial asthma, stammering, poor appetite, and proneness to bone fractures, not to mention mental-health issues such as school phobias, youth suicides, and even the advent of perhaps the greatest social menace of the 21st Century: the Hikikomori.

(In Japan) A person’s value is contingent upon their ability to conform to the norms of society. However, hikikomori are unable to conform; therefore they feel completely useless

~ Teppei Sekimizu

Hikikomori (引きこもり)

Literally translating as “pulling inward, being confined,” this acute mental condition results in a complete withdrawal away from people. These societal recluses, which include both Japanese youth as well as the middle-aged, have been estimated in excess of a million people. Until recently, although hikikomori may have been embarrassments to their families, they were pretty much viewed as harmless. Nonetheless, in the spring of 2019, in the wake of some tragic murders which occurred in the Tokyo area, public opinion has been changing concerning this mental-health condition. Hideaki Kumazawa, a 76-year-old retired bureaucrat from the Agriculture Ministry, stabbed his 44-year-old son, Eiichiro, to death. Mr. Kumazawa claimed it was his duty to kill his son in order to prevent another violent outbreak such as the one which occurred on May 28, in Kawasaki City. On that fateful morning, a 57-year-old man—who was alleged to be hikikomori—stabbed 17 people, resulting in 2 deaths before also killing himself. Since then, hikikomori in their 40s and 50s (with parents in their 70s and 80s), have been a target for media attention. Dr. Carla Ricci, an anthropologist and researcher at the Department of Clinical Psychology at the University of Tokyo, searched for hikikomori in Italy and discovered a case in the southern part of the country. Since Italians are not known for having a stressful work society, she searched for something else the two countries shared in common. Dr. Ricci claims that, similar to Japan, Italian households tend to be matriarchal. Could the pressure exacted by overbearing Japanese mothers be to blame for millions of socially inept offspring who may later develop violent behavior?

Hideaki Kumazawa, a 76-year-old retired bureaucrat from the Agriculture Ministry, stabbed his 44-year-old son, Eiichiro, to death. Mr. Kumazawa claimed it was his duty to kill his son in order to prevent another violent outbreak such as the one which occurred on May 28, in Kawasaki City. On that fateful morning, a 57-year-old man—who was alleged to be hikikomori—stabbed 17 people, resulting in 2 deaths before also killing himself. Since then, hikikomori in their 40s and 50s (with parents in their 70s and 80s), have been a target for media attention. Dr. Carla Ricci, an anthropologist and researcher at the Department of Clinical Psychology at the University of Tokyo, searched for hikikomori in Italy and discovered a case in the southern part of the country. Since Italians are not known for having a stressful work society, she searched for something else the two countries shared in common. Dr. Ricci claims that, similar to Japan, Italian households tend to be matriarchal. Could the pressure exacted by overbearing Japanese mothers be to blame for millions of socially inept offspring who may later develop violent behavior?

Mind Playing Tricks

Many of us have no problem going on vacation (or living) in urban areas with high crime rates like NYC, London, or Paris as long as we stay in buildings equipped with gates, alarms, and security-cameras. Once inside our locked doors we feel pretty safe. However, what if the stress of this world became so great—so unbearable—that you started hearing voices telling you to kill yourself? How could you possibly hope to protect yourself from yourself?

I’ve had the pleasure to teach and coach sports in more than a few schools and universities throughout Japan. Overall, my teaching experience has been very rewarding; however in every school where I worked, at some point, there was talk about a student (or teacher) who was contemplating suicide. Many people know that Japan has a special relationship with suicide, but most are unaware to what extent. Let’s put it like this: if there are less than 30,000 suicides committed annually, Japan considers this a good year. 30,000 deaths! In 2014, it was reported that, on average, 70 people committed suicide every day! Please understand that ritualized death has been historically woven into the fabric of Japanese society, therefore there are various categories and some of them are considered honorable.

Death Culture

According to the late author/actor, Yukio Mishima, who disemboweled himself in what is probably the most publicized suicide in Japanese history, seppuku (切腹) differs from “the western concept of suicide.” Originally reserved for samurai families, eventually it became a method for people of any class to restore honor for themselves or their family. Most people are aware of the Kamikaze pilots during World War II who became renowned for crashing their planes into the enemy ships. In addition to seppuku, there are several death-ritual categories not commonly found outside of Japan such as shidoshi (指導死), which is students who kill themselves as a result of teachers being too strict; or karoshi (過労死), which is death from overwork. Another popular category is Shinjū (心中), which are suicide pacts formed among individuals. Nowadays, the victims are usually strangers but traditionally, especially in the bunraku puppet theaters of the 17th century, this final-act was undertaken by two people bound by love—typically lovers or parent and child. The more contemporary version, which may include more than two people, has become so popular it has been dubbed “Internet Group Suicide.”

These people share in common a longing to end the suffering called life; and therefore, they vow to end theirs together at the same time, using the same method. The ever-increasing popularity of these pacts have resulted in the rise of famous “suicide areas” where police constantly patrol in an attempt to catch victims before they can fulfill their grim objectives. A forest at the base of Mount Fuji, called Aokigahara, reported 247 suicide attempts in 2010. Another such site in Fukui Prefecture, Tōjinbō, is a series of cliffs along the Sea of Japan. Legend claims that a Buddhist priest named Tōjinbō was disliked by the townspeople so much they threw him off the 70-foot-high cliffs and his spirit still haunts the area. Yukio Shige, a retired police officer, took it upon himself to patrol the cliffs, and in 2015 reported that his efforts saved over 500 lives. Railroad tracks have become such a common place for suicide that in an attempt to decrease incidents, Japanese railroad companies have installed chest-high track barriers as well as blue-tinted lights which are intended to calm people’s moods. As a further deterrent, there is a hefty fine to be paid by the surviving family members of anyone who commits suicide by laying down on the tracks for “the disruption of service.”

These people share in common a longing to end the suffering called life; and therefore, they vow to end theirs together at the same time, using the same method. The ever-increasing popularity of these pacts have resulted in the rise of famous “suicide areas” where police constantly patrol in an attempt to catch victims before they can fulfill their grim objectives. A forest at the base of Mount Fuji, called Aokigahara, reported 247 suicide attempts in 2010. Another such site in Fukui Prefecture, Tōjinbō, is a series of cliffs along the Sea of Japan. Legend claims that a Buddhist priest named Tōjinbō was disliked by the townspeople so much they threw him off the 70-foot-high cliffs and his spirit still haunts the area. Yukio Shige, a retired police officer, took it upon himself to patrol the cliffs, and in 2015 reported that his efforts saved over 500 lives. Railroad tracks have become such a common place for suicide that in an attempt to decrease incidents, Japanese railroad companies have installed chest-high track barriers as well as blue-tinted lights which are intended to calm people’s moods. As a further deterrent, there is a hefty fine to be paid by the surviving family members of anyone who commits suicide by laying down on the tracks for “the disruption of service.”

Conclusion

As I collected information for this article, I checked out several suicide-prevention websites. Each of them preached the same window-dressing remedies of education, investing in research, and communication; but nothing addressed the huge, nasty elephant in the room. No one wants to assign blame to, nor shoulder any responsibility for (their participation in), a sick, biased society…a death culture. Acute social-withdrawal is not temperamental shyness but, rather, it’s a marked change in which an individual used to be engaged with family and friends and, due to some form of trauma, she/he suddenly decides to withdraw away from people. Dr. Thomas Joiner, author of Why People Die, calls this “an inward gaze of bemused resignation and resolution.”

Understanding there are virtually no ghettos or slum areas in Tokyo or Osaka, it’s easy to compare Japan’s Hikikomori crisis with the homeless situation in most western countries; both have turned away from society and both are seen as pariahs. What could be so traumatizing about the society in a (so-called) developed country that it results in millions of people throwing in the towel and giving up?

Hmm, I think that brings us back to the stinky elephant in the room.

Note: This is only one of topics that will be covered (in more detail) in the upcoming book: Modern Japan—decoded!

Takuan Amaru is the author of the trilogy, Gaikokujin – The Story.

Reference

Thomas Joiner, Why People Die by Suicide (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2006).