Back in 2018, when Naomi Osaka defeated Serena Williams in the U.S. Open to secure her first Grand Slam victory, there was much discussion over Naomi’s racial identity. “Is she Black? Is she Japanese? Is she Haitian? Is she American? Actually, I saw very little discussion over her Haitian heritage, which I found surprising. In recent years, there have been other Black-Japanese stand-outs such as Ariana Miyamoto, who in 2015 received her share of media attention following her nomination as Miss Japan and her subsequent appearance in the internationally televised Miss Universe pageant. Or Rui Hachimura, who was named to the 2020 All-NBA second team; he is another rising star known by most sports fans both inside and outside of Japan.

Since I spent much of my youth on a basketball court, it is easy for me to cheer for the young brother from Toyama, and Miss Miyamoto too. However I feel a special kinship with Naomi Osaka because unlike Rui and Ariana who were born and raised in Japan, the Osaka family moved to the United States while the two girls, Mari and Naomi, were still small children. It was in Long Island and, later, South Florida, where Naomi and her elder sister spent a significant part of their formative years.

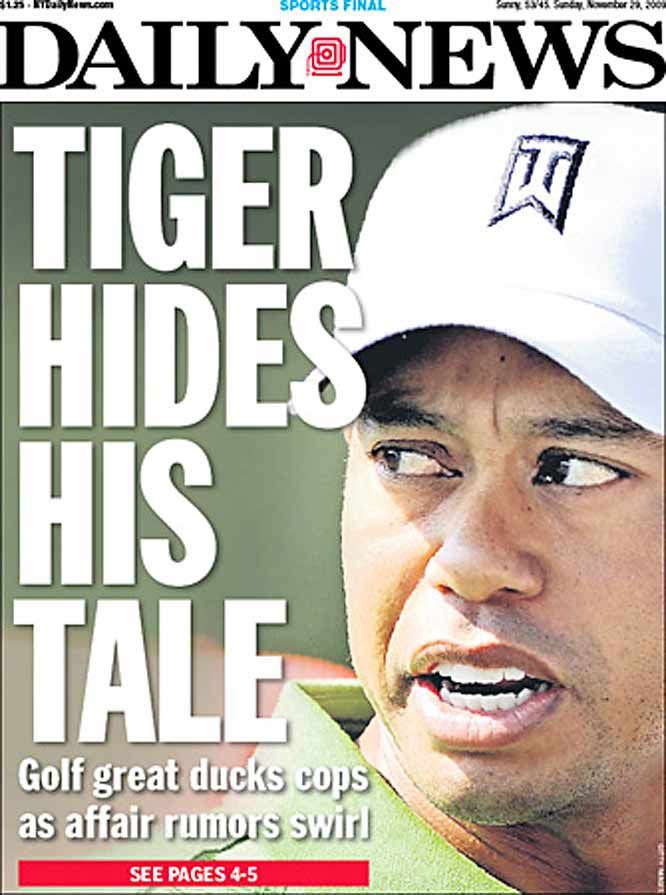

When responding to questions about her ethnicity, Naomi does not feel the need to divide her bloodline into divisible segments with terms like “half” or “quarter.” She also does not attempt to side-step or make herself ‘less threatening’ to the dominant society. Her description is humble and straight to the point: “My dad’s Haitian, so I grew up in a Haitian household in New York. I lived with my grandma. And my mom’s Japanese, and I grew up with the Japanese culture, too. And if you’re saying American, I guess because I lived in America, I also have that, too.” Please notice her repeated usage of the word ‘too,’ which denotes synergy and confluence, rather than the limitations implied by the divisive phrases above. Think about it: how can a person occupy only half of or quarter of a race? However there are people of ‘mixed-race’ ancestry who disagree. It is no secret that Tiger Woods has coined special terminology to explain his ethnic composition. Tiger calls himself a “Cablinasian,” which is his own syllabic abbreviation for Caucasian, Black, American Indian, and Asian. Hmm, can we just chalk this up as Tiger saying: ‘Anything is better than being black’? Even though his father is clearly a black man, this is how Tiger chooses to describe himself to the media. Naomi, on the other hand, was quick to pay homage to her father’s Haitian heritage.

Is it not true that sometimes, in life, the answer to the question is not A, B, or C but, rather, ‘All of the Above?’

For Black-Asian kids growing up in the United States, from early childhood, we are confronted with this racial-identity dilemma, mostly by our friends. Although our situations may seem identical to people observing us from the outside, depending on which parent is black and the demographics of the neighborhood where a child is living, this may not be so. The first time I met a Black-Japanese boy whose mother was Black and father was Japanese, I realized how different his experience was from those of us with black fathers. An even bigger surprise were the kids who resembled me but somehow made the decision to identify as white. Now, if they were asked about their racial identity, they might have responded with ‘mixed race’ or ‘half this and half that’ but by their demeanor, speech patterns, friends, etc., it was clear they had nothing to do with black folks. And this is okay. It was just confusing. Believe it or not, many of them were just as puzzled by my black demeanor, speech patterns, and almost exclusively black friends. In the mid-90s, when the ‘Golden Age of Hip Hop’ was at its apex, never was there a cooler time to be black! Back then, a few of my Asian-Black brethren from childhood called me and expressed a desire to link-up. Being in town during semester breaks from university, I would oftentimes stop by to watch ball games with them over a few beers. Although I remember these moments as good times, I soon realized a few of them had an ulterior motive for hanging-out with me: they wanted to break the code on ‘how to be black.’ They really believed I was acting in some unnatural way, or had learned how to do something ‘special’ in order to gain the trust and familiarity of people in the hood.

Are Black-Japanese included in the Haafu Community?

Haafu (ハーフ) is a Japanese term used to refer to an individual born to one ethnic Japanese and one non-Japanese parent. A loanword from English, the term literally means ‘half,’ and is a reference to the individual’s non-Japanese heritage. The overwhelming majority of people who identify as haafu have a white parent in the mix. Some notable actresses who receive media attention are Hayley Kiyoko Alcroft, Minami Bages, and Nichole Bloom. There are social-media groups among the various platforms with Haafu in their name. Following Naomi’s victory over Serena in 2018, in my celebratory post, I remember getting attacked on one of these sites after I referred to Ms. Osaka as a ‘Black woman.’ One of the people who took exception was a white woman with Japanese grandparents. She expressed outrage because she claimed Naomi was not black, she was a haafu—like her. In the DM I received, the lady actually accused me of being a racist. This prompted me to find out more information; I wanted to know why she felt so close to the tennis star. It turns out this woman was raised in a small town in the rural Midwest of the United States. She readily admits she has had very little interaction with blacks throughout her life and that, in addition, her experience in Japan is limited to “four adorable New year’s holidays with obaachan (her grandmother).”

Understanding this, I simply stated the obvious, which was that she has absolutely nothing in common with Naomi Osaka…and definitely less than the average black woman. And, of course, she flatly refused this suggestion, especially the last part. “Naomi grew up in a Haitian household, in New York of all places,” I argued, “while you grew up an exclusive, upscale neighborhood in the Midwest.” Okay, I admit it, the real reason the lady became angry and called me a racist was due to my final comment: “Basically, you’re just a white woman who can use chopsticks.” While my words were far from flattering, does any of it qualify as racism? Or, is this just another ‘Karen’ out in the wilderness attempting to exercise her “I’m white and I say so” privilege?

For me, the idea of being ‘half’ of a race has always been akin to derogatory slave terminology like mulatto, quadroon, or octoroon. It was not until I reached well into adulthood and traveled to the Caribbean and the continent of Africa, when I realized it was the belief in such ideology and the associated pejorative terms which were behind the tendency for my Asian-Black buddies to gravitate towards white social circles, as well as why a white woman living out in the sticks must insist Naomi is not a black woman in order to believe she shares something in common with her. This color-coded caste system, which is based on bloodlines as well as complexion, is very strict in some countries of Africa, India, and the islands in the West Indies. In the United States, there has always been some level of pitting the light-skinned against the dark-skinned too, such as what I call the “good hair epidemic” or the infamous “Brown Paper bag Test.” However, at the end of the day, American blacks know when po-po—i.e. the ‘good ol boys’—are racially profiling their victims, or job applications and bank loans are being denied, those with high-yellow skin and wavy hair are not being filtered-out or given a pass. Put more simply, since his first automobile accident in 2009, how do you think Tiger Woods has been treated by the media? Like an average (white) athlete?

Once his sex scandal hit the press, Tiger has had a serious fall from grace. Following his most-recent accident, there has been a wave of sympathetic support and I, too, hope he’s healing nicely; but let’s face the facts. Nowadays Tiger gets abused by the media the same as Colin Kaepernick did, which is the same way the media tried to punish Naomi following her withdrawal from the French Open. Should we call this the Cablinasian treatment?

No, no, it is the same tried-and-true method of marginalization that sports analysts like Stephen A. Smith butter their bread with—it’s the same old Ni99a treatment!

Takuan Amaru is the author of the trilogy, Gaikokujin—The Story.