Japan is a strange country

~Jonathon Rice, author of Behind the Japanese Mask

As a child growing up in the United States, I got teased more than once due to my mother being Japanese. I’ll never forget the time my friend, Terrence, and I went to my house for some ice cream. As I was getting the ice cream out of the freezer, Terrence shrieked in terror.  Taken totally by surprise, I looked at the shelf above the ice cream to where he was pointing and, to my dismay, spotted a frozen octopus. To make matters worse, the very next day—while Terrence just happened to be walking down my street—a big truck drove around the corner and parked in our driveway. Reading the words “Fresh Fish” written above the image of a salmon being scooped into a net, I cringed knowing that this was just another example of something which only occurred at my house. While we’re on the topic allow me to mention that, aside from the truck that came to our house, to this day, I’ve never seen a seafood home-delivery service. Have you?

Taken totally by surprise, I looked at the shelf above the ice cream to where he was pointing and, to my dismay, spotted a frozen octopus. To make matters worse, the very next day—while Terrence just happened to be walking down my street—a big truck drove around the corner and parked in our driveway. Reading the words “Fresh Fish” written above the image of a salmon being scooped into a net, I cringed knowing that this was just another example of something which only occurred at my house. While we’re on the topic allow me to mention that, aside from the truck that came to our house, to this day, I’ve never seen a seafood home-delivery service. Have you?

The next week, at school, when Terrence yelled “Freeeshh Fiiish” down the hallway—making sure to stretch each word in a sarcastic tone—followed by my friends busting-out laughing, I imagined he had told everyone about both the ice cream incident and the truck. “Oh, you wanna crack jokes?” I said after walking up to him and the rest of my friends. And then I proceeded to make the same mistake I always made in this situation. Being a confident kid who was blessed with the gift of gab when it came to playing “the Dozens,” I repeatedly fell into the trap of trying to defend Japan by talking about weird things Americans do. Talk about a bad strategy! Why, you ask? Because this always led to what I call “Ching-chong” jokes.  The subject-matter for this type of satire encompasses all Asian stereotypes but usually centers on something “China-like,” such as movies with Jackie or Charlie Chan, or even Fu-Manchu. Suffice to say, they really used to laugh-it-up at my expense. Back then, I would get angry knowing that the majority of their references were not even Japanese. That said, in 2019, when I reminisce on losing those battles with my buddies, I count my blessings none of this occurred during the Age of the Internet when they would have had access to actual facts and visuals on Japan that really are embarrassing! Facts like back in 2016 when Godzilla was granted citizenship in Tokyo; and visuals such as Japanese eating what appears to be live squid while the tentacles are still moving. This spectacle really seems to freak westerners out. Another Japanese favorite that bewilders me—and I know some may disagree—is this irrational obsession with all things “kawaii.” I am specifically referring to the ever-expanding horde of furry mascots which make appearances at local events, shrines, festivals, or even on television. Many people look at me sideways for what they consider to be condemning Japan’s Kawaii Culture. “What’s wrong with a person falling in-love with his or her own conception of cuteness?” one of my students responded on behalf of the animated creatures. And I agree with this sentiment to a point; so let’s unpack this.

The subject-matter for this type of satire encompasses all Asian stereotypes but usually centers on something “China-like,” such as movies with Jackie or Charlie Chan, or even Fu-Manchu. Suffice to say, they really used to laugh-it-up at my expense. Back then, I would get angry knowing that the majority of their references were not even Japanese. That said, in 2019, when I reminisce on losing those battles with my buddies, I count my blessings none of this occurred during the Age of the Internet when they would have had access to actual facts and visuals on Japan that really are embarrassing! Facts like back in 2016 when Godzilla was granted citizenship in Tokyo; and visuals such as Japanese eating what appears to be live squid while the tentacles are still moving. This spectacle really seems to freak westerners out. Another Japanese favorite that bewilders me—and I know some may disagree—is this irrational obsession with all things “kawaii.” I am specifically referring to the ever-expanding horde of furry mascots which make appearances at local events, shrines, festivals, or even on television. Many people look at me sideways for what they consider to be condemning Japan’s Kawaii Culture. “What’s wrong with a person falling in-love with his or her own conception of cuteness?” one of my students responded on behalf of the animated creatures. And I agree with this sentiment to a point; so let’s unpack this.

The Mayor of Shiki City presents “Kapal” with a special resident’s card.

Perhaps it’s harmless to be infatuated with over-sized munchkins if you’re still in elementary school but these fuzzy characters are more beloved and adored by adults than children. And this fascination with childishness, in my opinion, lends itself to more debased, juvenile-related idiosyncrasies such as Lolicom, which is the Japanese abbreviation for the “Lolita complex.” This is the term for Manga and Anime featuring sexually explicit images of children. Lolicom can involve extreme violence, rape, and incest; therefore it’s not hard to link it with the social pathology known as Chikan 「痴漢, チカン, or ちかん」. This is the act of being sexually fondled / raped in public by strangers. So at the end of the day I guess it’s true: Japan is indeed a weird place to live.

Want to be Japanese?

Back in junior-high school, as I was experiencing the teenage challenges associated with adolescence, I vowed to return to Japan later in life—foolishly believing, at that time, I would’ve been able to escape peer pressure had I lived with my cousins. Therefore, when I finally did arrive, similar to some expats and Japanophiles, I had unrealistic, starry-eyed visions of totally relinquishing western culture and immersing myself in Japanese society. For anyone from the western hemisphere, the first impression of Japan can appear quite attractive for many reasons. At the top of the list has to be the clean, orderly streets and neighborhoods which,  for the most part, are free of debris, criminals, and even homeless people. “The streets here are so clean that you can eat off the ground!” is how one American singer who lived in Shizuoka told me back in 1999. And this strong hygienic-ethic is upheld everywhere from parks and rivers, to public restrooms (even those in convenience stores and subway stations).

for the most part, are free of debris, criminals, and even homeless people. “The streets here are so clean that you can eat off the ground!” is how one American singer who lived in Shizuoka told me back in 1999. And this strong hygienic-ethic is upheld everywhere from parks and rivers, to public restrooms (even those in convenience stores and subway stations). In addition, for people sporting a melanin-rich hue like mine, it is reassuring to know that racial-profiling by police doesn’t come close to comparing with the U.S. or U.K. More importantly, even if I am stopped by five-oh, I’m not fearful of being attacked or killed when I reach for my I.D. or driver’s license.

In addition, for people sporting a melanin-rich hue like mine, it is reassuring to know that racial-profiling by police doesn’t come close to comparing with the U.S. or U.K. More importantly, even if I am stopped by five-oh, I’m not fearful of being attacked or killed when I reach for my I.D. or driver’s license.

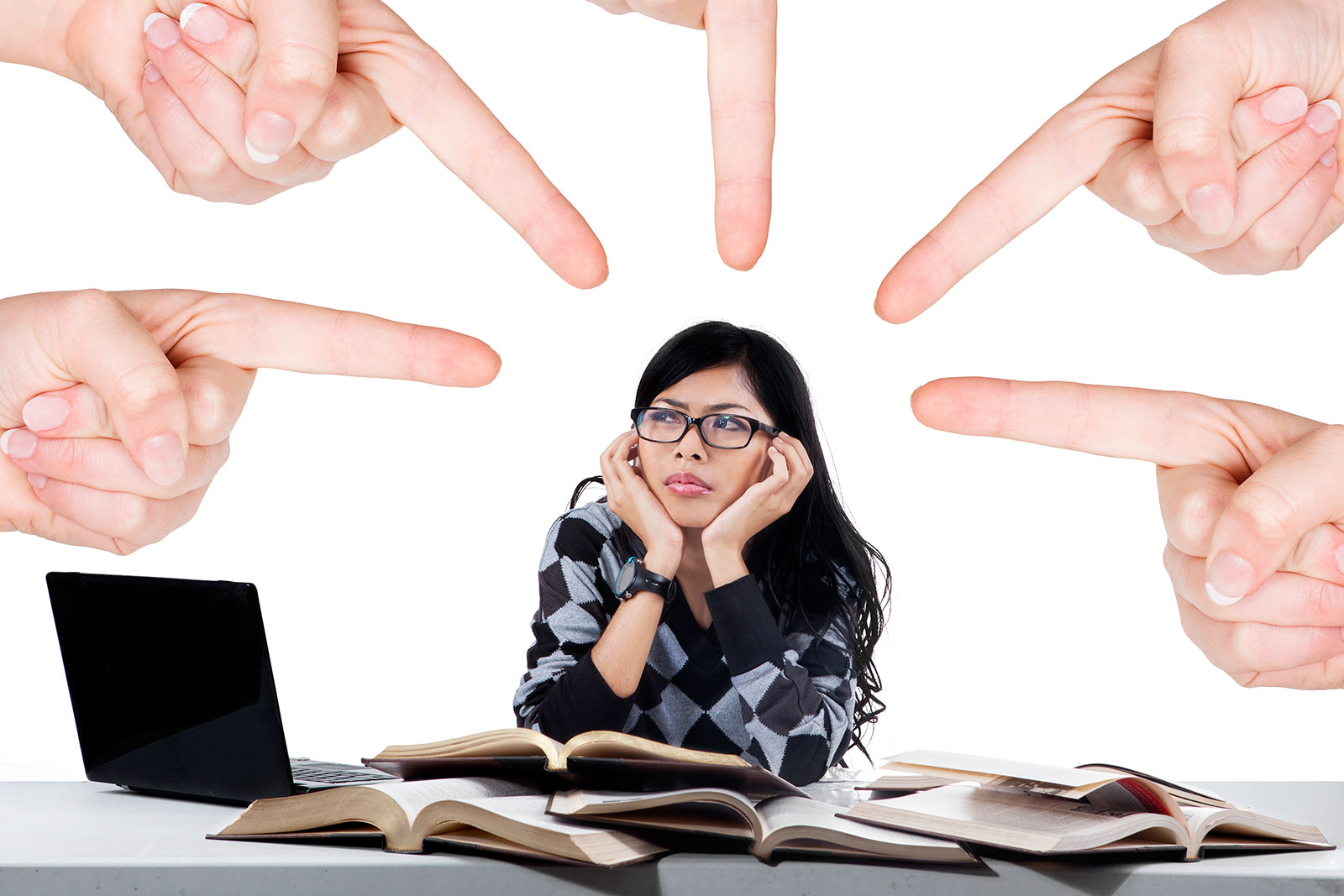

For years, I was lulled to sleep by my sanitary, shiny surroundings and the quiet, incident-free train rides to and from work. Then, one day, on my normal Osaka – Kyoto commute on the Keihan Railway (which has to be the slowest train in Japan), just as I was drifting off to sleep, an ‘a-ha moment’ hit me so hard I was suddenly jarred wide-awake. Removing my headphones, I noticed that aside from the public announcements and the jolting movements of the train as we glided down the tracks, like always, there was barely any noise at all. Japanese are reserved by nature—okay I get that—but on such a crowded train during rush hour it was too quiet. And like I said, it was always too damn quiet! I now realized that what I initially mistook for peace and tranquility was actually more comparable to the imposed silence and depression in a concentration camp. To confirm my theory, I glanced around at some of the other passengers from my seat—even though I knew this was taboo.  As soon as I committed this social gaffe everyone, it seemed, turned in my direction and trained their eyes on me. Although they only stared, I could’ve sworn they were at least pointing, if not spitting and hurling insults—this is how much I felt their resentment. Suddenly, the incessantly repeating announcements instructing passengers to be quiet, and to put their cell-phones on manner-mode so as to “not bother anyone nearby,” sounded louder than ever. Feeling claustrophobic, I stood up and grabbed my bag before navigating through the crowd toward the exit of the still-moving train. Although I did not feel physically threatened, I was now painfully aware of the severe level of anxiety around me. It felt like I was suffocating so I just wanted to change locations. After finding a vacant area near the door, I leaned back, took a deep breath, and just stared out the window as blurred images of houses, parking lots, and pachinko parlors whizzed by.

As soon as I committed this social gaffe everyone, it seemed, turned in my direction and trained their eyes on me. Although they only stared, I could’ve sworn they were at least pointing, if not spitting and hurling insults—this is how much I felt their resentment. Suddenly, the incessantly repeating announcements instructing passengers to be quiet, and to put their cell-phones on manner-mode so as to “not bother anyone nearby,” sounded louder than ever. Feeling claustrophobic, I stood up and grabbed my bag before navigating through the crowd toward the exit of the still-moving train. Although I did not feel physically threatened, I was now painfully aware of the severe level of anxiety around me. It felt like I was suffocating so I just wanted to change locations. After finding a vacant area near the door, I leaned back, took a deep breath, and just stared out the window as blurred images of houses, parking lots, and pachinko parlors whizzed by.

From that day onward I’ve been keenly aware of an intangible cloud of depression, despair, and loneliness that hovers over Japan.  Unlike in the Americas, where life’s challenges are so tangible and direct they might slap you in the face (i.e. police brutality or getting mugged), Japan is a world of illusion: nothing is ever what it appears to be. Many issues that seem insignificant due to their passive, kawaii packaging may be, in reality, as constant and never-ending as the “Chinese Water Torture.” For example, Japanese are inundated with simple obligations such as exchanging winter-holiday greetings called Nenkajo (年賀状), or buying Omiyage (お土産), which are souvenirs for friends and co-workers while on a trip. From these descriptions, both customs seem like nothing more than amicable gestures. That is until one realizes they are obligatory—not optional. And furthermore, there are several times a year when etiquette dictates the exchange of gifts—not just on New Years and the occasional business trip. Again, it cannot be emphasized enough how Japanese constantly feel pressure to fulfill a plethora of responsibilities. To do otherwise would be to lose face. And since these duties to their family, company, school, or even town are persistent and without end, over a period of time, they have a tendency to wear down even the strongest wills.

Unlike in the Americas, where life’s challenges are so tangible and direct they might slap you in the face (i.e. police brutality or getting mugged), Japan is a world of illusion: nothing is ever what it appears to be. Many issues that seem insignificant due to their passive, kawaii packaging may be, in reality, as constant and never-ending as the “Chinese Water Torture.” For example, Japanese are inundated with simple obligations such as exchanging winter-holiday greetings called Nenkajo (年賀状), or buying Omiyage (お土産), which are souvenirs for friends and co-workers while on a trip. From these descriptions, both customs seem like nothing more than amicable gestures. That is until one realizes they are obligatory—not optional. And furthermore, there are several times a year when etiquette dictates the exchange of gifts—not just on New Years and the occasional business trip. Again, it cannot be emphasized enough how Japanese constantly feel pressure to fulfill a plethora of responsibilities. To do otherwise would be to lose face. And since these duties to their family, company, school, or even town are persistent and without end, over a period of time, they have a tendency to wear down even the strongest wills.

Daily Life = Stress Overload

Over the years, some of my private English lessons have gradually morphed into something closer to psychotherapy consultations. I imagine these counseling sessions, which have been occurring more frequently as of late, have less to do with my experience as a social worker and more about the fact that most Japanese don’t feel comfortable enough to discuss (Japanese) issues with either people who they believe know nothing about their culture, i.e. foreigners, or those who are fully-integrated into their society, i.e. a born-and-bred Japanese. It seems I am regarded as being somewhere in the middle. One of these students, a married woman in her late-30s, told me that whenever her husband goes on business trips she is required to spend a couple hours each day with her mother-in-law. Although it is done under the pretext of helping her husband’s mother with cooking, cleaning, shopping, etc., the woman told me she knows it’s just an excuse for the mother-in-law to be nosy and to keep an eye on her. While it’s true that over-bearing mother-in-laws are not unique to Japan, I’ve never heard of them (across the board) wielding so much power. In addition, the same lady oftentimes complains about the numerous Shinto or Buddhist rites that fall on certain days which, in addition to a financial contribution, also require a visit to a consecrated place like a shrine or temple. To be honest, for over a year, I wrote her off as nothing more than a whiner, especially when one of her distant relatives died and she was moaning about the Buddhist ceremonies called Shonanoka (初七日) and Shijūkunichi (四十九日), which are rituals held on the 7th and the 49th day after the death. But then, I began to reflect on how any extra obligations she incurs are in addition to her 8-hour work day as an OL (Office Lady); and since her husband has a 10 – 14 hour work-day—plus mandatory drinking parties after-work—it is just as hectic for him too. ![—cŽ™‚Qlæ‚é“d“®Ž©“]ŽÔ](https://takuanamaru.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/mom-and-kids-on-bike.jpg) Although women normally have a shorter work-day and fewer after-work responsibilities than men, this is only because it is understood they have housewife duties waiting at home which include picking-up and rearing the children all by herself. In Nippon Series 9, we examined some of the consequences of surviving in such a stressful environment such as karoshi (death from overwork), jisatsu (suicide), and hikikomori (vagabond hermitage); so in this edition we shall examine a few of the unique and—I might as well just say it—weird ways Japanese choose to combat their own feelings of isolation and stress.

Although women normally have a shorter work-day and fewer after-work responsibilities than men, this is only because it is understood they have housewife duties waiting at home which include picking-up and rearing the children all by herself. In Nippon Series 9, we examined some of the consequences of surviving in such a stressful environment such as karoshi (death from overwork), jisatsu (suicide), and hikikomori (vagabond hermitage); so in this edition we shall examine a few of the unique and—I might as well just say it—weird ways Japanese choose to combat their own feelings of isolation and stress.

Rent-A-Family (レンタル家族)

It’s extremely strange to me that people would want to rent families, and even more surprising that they seem to be satisfied

~Dr. Takeshi Sato, Sociology professor, Hitotsubashi University.

A Rental Family Service or Professional Stand-In Service sends actors to spend time with their clients. Normally, the actors go the client’s home; but occasionally they attend social events such as weddings or other public ceremonies. Since the actors portray the client’s family members, friends, or coworkers, this allows the client to exist in a temporary, superficial world of illusion where they have positive relationships and are the center of attention. “I suppose people nowadays really find the need for kinship.  Compared to 50 years ago, the family system in Japan has really changed, and family-like relationships are gradually disappearing,” commented Dr. Sato in an attempt to explain this phenomenon. Since these services started popping up during the early 1990s, by now, many people have gotten used to them. For this reason, it seems, Japan felt the need to move the “strangeness bar” up a notch higher; and low and behold, they did it with their newly introduced, “Do-Nothing Services.” Called 「レンタルなんもしない人」 or just 「何もしないを職業」 in Japanese, these agencies send people to clients just like the rental-family-services; however unlike the previously mentioned establishments, these employees are paid to do nothing except show up—that’s right absolutely nothing. They literally just stand next to, or sit with, the client and do nothing except provide quiet company; they don’t even talk! How lonely does a person have to be before they start contemplating on hiring a complete stranger to accompany them to the mall? Or sit across from them (quietly) in a coffee shop? For those who have never lived here, it’s almost impossible to understand to the degree in which Japanese have been indoctrinated with a “group-only” mentality. Put another way, an individual has very little value in this society; his/her worth is equivalent to the reputation of their family, school, company, or other affiliation.

Compared to 50 years ago, the family system in Japan has really changed, and family-like relationships are gradually disappearing,” commented Dr. Sato in an attempt to explain this phenomenon. Since these services started popping up during the early 1990s, by now, many people have gotten used to them. For this reason, it seems, Japan felt the need to move the “strangeness bar” up a notch higher; and low and behold, they did it with their newly introduced, “Do-Nothing Services.” Called 「レンタルなんもしない人」 or just 「何もしないを職業」 in Japanese, these agencies send people to clients just like the rental-family-services; however unlike the previously mentioned establishments, these employees are paid to do nothing except show up—that’s right absolutely nothing. They literally just stand next to, or sit with, the client and do nothing except provide quiet company; they don’t even talk! How lonely does a person have to be before they start contemplating on hiring a complete stranger to accompany them to the mall? Or sit across from them (quietly) in a coffee shop? For those who have never lived here, it’s almost impossible to understand to the degree in which Japanese have been indoctrinated with a “group-only” mentality. Put another way, an individual has very little value in this society; his/her worth is equivalent to the reputation of their family, school, company, or other affiliation.

Some stress-release systems which are not so odd but may only have a real foothold in Japan are Host/Hostess Clubs, Kyabakura 「キャバクラ」, “Snack” 「スナック」 bars, and the newly popular Aiseki-izakayas 「相席居酒屋 」. All of these are varying levels (as far as price and quality) of lounges where clients pay to be catered to by the opposite sex. Established in the late 1960s, even before the Economic “Bubble” (in the 80s) this type of entertainment had already become a staple of Tokyo nightlife. Everyone I spoke with agreed that nowadays these clubs are so widespread they are considered a custom or tradition among Sararimen. If you are interested in further details there is so much information available on the first three clubs, but not so much on the newest kid on the block. Aiseki-izakayas are pubs where people who are seeking a romantic partner are paired with a complete stranger of the opposite sex. Over simple dishes and alcoholic beverages, the two talk and get to know each other.

Evidently there is a fortune to be made by capitalizing on the loneliness and isolation that many Japanese feel. For a nation obsessed with group ethics, Japanese pay top-dollar to escape the rigid parameters they impose on themselves and each other. This feeling of being trapped, in many cases, leads to forms of entertainment which satisfy the lower, more base (and oftentimes concealed) desires—especially in the sex industry.

Cuddle Cafes

The first Cuddle Cafes opened in Tokyo in 2012. Called Soine-ya 「ソイネ屋」, which in Japanese literally means “sleep-together shop,” these venues provide male customers the opportunity to sleep next to a beautiful woman for a fee. According to one article I found about shops in Akihabara, Tokyo, prices range from a 20-minute nap for ¥3,000 ($38 USD) to a 10-hour full-night-sleep package for ¥50,000 ($640 USD).  However, there are options as well. If you want to choose which girl you want to sleep with, it is an additional ¥1,000 plus another ¥500 for each hour. Moreover, if you want to sleep on the girl’s lap, that’s another ¥1,000; and if you want her to sleep on your lap, the price doubles to ¥2,000. Although the sites I perused emphatically state there is no sexual activity occurring, when you look at some of the available choices such as stroking the girl’s hair, staring in each other’s eyes for 1 minute, or giving/receiving special types of caressing—plus the women are attired in panties and sexy nightgowns—it is beyond my understanding how this does not lead to intercourse.

However, there are options as well. If you want to choose which girl you want to sleep with, it is an additional ¥1,000 plus another ¥500 for each hour. Moreover, if you want to sleep on the girl’s lap, that’s another ¥1,000; and if you want her to sleep on your lap, the price doubles to ¥2,000. Although the sites I perused emphatically state there is no sexual activity occurring, when you look at some of the available choices such as stroking the girl’s hair, staring in each other’s eyes for 1 minute, or giving/receiving special types of caressing—plus the women are attired in panties and sexy nightgowns—it is beyond my understanding how this does not lead to intercourse.

Creepy or curious – you decide. It’s undoubtedly weird, however.

~Nicci Martel

Hentai Comics

From a young age, I was exposed to Shunga art from the Japanese magazines lying around our house; so I knew that compared to Caucasians, Japanese had a much more liberal perspective on sex and the (naked) human body.  That said, the porn industry in Japan is a dark, vast, bottomless pit which goes deeper than the average person can imagine—way down into a diabolical, hellish realm which can only be described with adjectives like obscene, ghoulish, or even macabre. For this reason, we are only going to skim the surface of this topic. By now (from the Internet), we should all be aware that what may be considered nasty, lewd, or indecent to some is sure to be described by others as suggestive, seductive…even erotic. The word Hentai is composed of two a kanji characters: 「変」 , meaning weird, and 「態」, meaning appearance or condition, i.e. perversion. Although perverts are not limited to Japan, many of the images in these comics / anime are rarely, if ever, seen in western erotica. While Japanese (Tatamae) identifies Hentai Comics as “strange,” the real deal (Honne) is sexploitation thrives here like nowhere else in the world. Here are a few of the more popular fetishes from a very long list.

That said, the porn industry in Japan is a dark, vast, bottomless pit which goes deeper than the average person can imagine—way down into a diabolical, hellish realm which can only be described with adjectives like obscene, ghoulish, or even macabre. For this reason, we are only going to skim the surface of this topic. By now (from the Internet), we should all be aware that what may be considered nasty, lewd, or indecent to some is sure to be described by others as suggestive, seductive…even erotic. The word Hentai is composed of two a kanji characters: 「変」 , meaning weird, and 「態」, meaning appearance or condition, i.e. perversion. Although perverts are not limited to Japan, many of the images in these comics / anime are rarely, if ever, seen in western erotica. While Japanese (Tatamae) identifies Hentai Comics as “strange,” the real deal (Honne) is sexploitation thrives here like nowhere else in the world. Here are a few of the more popular fetishes from a very long list.

- Shibari 「縛り」 is a Japanese word that literally means “to tie decoratively.” It is a Japanese form of BDSM (bondage, discipline, dominance and submission) using ropes. Basically, it is a form of sadomasochism.

- Bukkake 「ぶっかけ」 is the act of having sex in which one participant is ejaculated on by two or more other participants. Although this, in and of itself, is not so strange by western standards, for it to be so popular in comics is bizarre.

- Gokkun「ゴックン」 is sexual activity in which a person consumes the semen of multiple men, usually from some kind of container.

- Omorashi 「おもらし / オモラシ / お漏らし」 is arousal from wetting yourself; or watching someone else do so.

- Shokushu Goukan 「触手強姦」 Since the translation of this is “Tentacle Violation,” “Tentacle Erotica” or “Tentacle Rape,” I’ll let you use your imagination for a description; nevertheless one question needs to be asked: what’s up with Japanese and octopus?

As I mentioned before, thank God my friends had not known about Hentai Comics back when they were making fun of that octopus in my freezer!

Conclusion

Becoming aware of the skyrocketing levels of stress and anguish lead to understanding why Japanese are so desperate for human contact.  There’s a saying: “Everything is okay in moderation.” However the strict, unforgiving rules in their world provide neither the time nor the luxury for sober self-restraint. This is because what is demanded of Japanese on daily basis almost forces them, in their few moments of free-time, to seek extreme methods to release their frustration. And it’s this type of desperation which sows the seeds for the weird sexual fetishes and other pathological behaviors which abound in Japan. It is also worth noting there is a large amount of research to substantiate the idea that problematic pornography use correlates with psychological problems such as depression and anxiety. I am not here to impose moral judgment on what is, or isn’t, an appropriate form of recreation but, rather, to direct attention to both the source and the consequences of the issue at hand. Recently, at a “Me Too” rally in Tokyo, a woman named Ms. Wakana Goto perfectly expressed my point: “In Japan, with its reputation as one of the world’s safest countries, I have been exposed to sexual harassment since the age of three, forced to get used to it, and to learn to deal with it.”

There’s a saying: “Everything is okay in moderation.” However the strict, unforgiving rules in their world provide neither the time nor the luxury for sober self-restraint. This is because what is demanded of Japanese on daily basis almost forces them, in their few moments of free-time, to seek extreme methods to release their frustration. And it’s this type of desperation which sows the seeds for the weird sexual fetishes and other pathological behaviors which abound in Japan. It is also worth noting there is a large amount of research to substantiate the idea that problematic pornography use correlates with psychological problems such as depression and anxiety. I am not here to impose moral judgment on what is, or isn’t, an appropriate form of recreation but, rather, to direct attention to both the source and the consequences of the issue at hand. Recently, at a “Me Too” rally in Tokyo, a woman named Ms. Wakana Goto perfectly expressed my point: “In Japan, with its reputation as one of the world’s safest countries, I have been exposed to sexual harassment since the age of three, forced to get used to it, and to learn to deal with it.”

Takuan Amaru is the author of Gaikokujin-the Story.

Takuan Amaru

Japan is a strange country

~Jonathon Rice, author of Behind the Japanese Mask

As a child growing up in the United States, I got teased more than once due to my mother being Japanese. I’ll never forget the time my friend, Terrence, and I went to my house for some ice cream. As I was getting the ice cream out of the freezer, Terrence shrieked in terror.  Taken totally by surprise, I looked at the shelf above the ice cream to where he was pointing and, to my dismay, spotted a frozen octopus. To make matters worse, the very next day—while Terrence just happened to be walking down my street—a big truck drove around the corner and parked in our driveway. Reading the words “Fresh Fish” written above the image of a salmon being scooped into a net, I cringed knowing that this was just another example of something which only occurred at my house. While we’re on the topic allow me to mention that, aside from the truck that came to our house, to this day, I’ve never seen a seafood home-delivery service. Have you?

Taken totally by surprise, I looked at the shelf above the ice cream to where he was pointing and, to my dismay, spotted a frozen octopus. To make matters worse, the very next day—while Terrence just happened to be walking down my street—a big truck drove around the corner and parked in our driveway. Reading the words “Fresh Fish” written above the image of a salmon being scooped into a net, I cringed knowing that this was just another example of something which only occurred at my house. While we’re on the topic allow me to mention that, aside from the truck that came to our house, to this day, I’ve never seen a seafood home-delivery service. Have you?

The next week, at school, when Terrence yelled “Freeeshh Fiiish” down the hallway—making sure to stretch each word in a sarcastic tone—followed by my friends busting-out laughing, I imagined he had told everyone about both the ice cream incident and the truck. “Oh, you wanna crack jokes?” I said after walking up to him and the rest of my friends. And then I proceeded to make the same mistake I always made in this situation. Being a confident kid who was blessed with the gift of gab when it came to playing “the Dozens,” I repeatedly fell into the trap of trying to defend Japan by talking about weird things Americans do. Talk about a bad strategy! Why, you ask? Because this always led to what I call “Ching-chong” jokes.  The subject-matter for this type of satire encompasses all Asian stereotypes but usually centers on something “China-like,” such as movies with Jackie or Charlie Chan, or even Fu-Manchu. Suffice to say, they really used to laugh-it-up at my expense. Back then, I would get angry knowing that the majority of their references were not even Japanese. That said, in 2019, when I reminisce on losing those battles with my buddies, I count my blessings none of this occurred during the Age of the Internet when they would have had access to actual facts and visuals on Japan that really are embarrassing! Facts like back in 2016 when Godzilla was granted citizenship in Tokyo; and visuals such as Japanese eating what appears to be live squid while the tentacles are still moving. This spectacle really seems to freak westerners out. Another Japanese favorite that bewilders me—and I know some may disagree—is this irrational obsession with all things “kawaii.” I am specifically referring to the ever-expanding horde of furry mascots which make appearances at local events, shrines, festivals, or even on television. Many people look at me sideways for what they consider to be condemning Japan’s Kawaii Culture. “What’s wrong with a person falling in-love with his or her own conception of cuteness?” one of my students responded on behalf of the animated creatures. And I agree with this sentiment to a point; so let’s unpack this.

The subject-matter for this type of satire encompasses all Asian stereotypes but usually centers on something “China-like,” such as movies with Jackie or Charlie Chan, or even Fu-Manchu. Suffice to say, they really used to laugh-it-up at my expense. Back then, I would get angry knowing that the majority of their references were not even Japanese. That said, in 2019, when I reminisce on losing those battles with my buddies, I count my blessings none of this occurred during the Age of the Internet when they would have had access to actual facts and visuals on Japan that really are embarrassing! Facts like back in 2016 when Godzilla was granted citizenship in Tokyo; and visuals such as Japanese eating what appears to be live squid while the tentacles are still moving. This spectacle really seems to freak westerners out. Another Japanese favorite that bewilders me—and I know some may disagree—is this irrational obsession with all things “kawaii.” I am specifically referring to the ever-expanding horde of furry mascots which make appearances at local events, shrines, festivals, or even on television. Many people look at me sideways for what they consider to be condemning Japan’s Kawaii Culture. “What’s wrong with a person falling in-love with his or her own conception of cuteness?” one of my students responded on behalf of the animated creatures. And I agree with this sentiment to a point; so let’s unpack this.

The Mayor of Shiki City presents “Kapal” with a special resident’s card.

Perhaps it’s harmless to be infatuated with over-sized munchkins if you’re still in elementary school but these fuzzy characters are more beloved and adored by adults than children. And this fascination with childishness, in my opinion, lends itself to more debased, juvenile-related idiosyncrasies such as Lolicom, which is the Japanese abbreviation for the “Lolita complex.” This is the term for Manga and Anime featuring sexually explicit images of children. Lolicom can involve extreme violence, rape, and incest; therefore it’s not hard to link it with the social pathology known as Chikan 「痴漢, チカン, or ちかん」. This is the act of being sexually fondled / raped in public by strangers. So at the end of the day I guess it’s true: Japan is indeed a weird place to live.

Want to be Japanese?

Back in junior-high school, as I was experiencing the teenage challenges associated with adolescence, I vowed to return to Japan later in life—foolishly believing, at that time, I would’ve been able to escape peer pressure had I lived with my cousins. Therefore, when I finally did arrive, similar to some expats and Japanophiles, I had unrealistic, starry-eyed visions of totally relinquishing western culture and immersing myself in Japanese society. For anyone from the western hemisphere, the first impression of Japan can appear quite attractive for many reasons. At the top of the list has to be the clean, orderly streets and neighborhoods which,  for the most part, are free of debris, criminals, and even homeless people. “The streets here are so clean that you can eat off the ground!” is how one American singer who lived in Shizuoka told me back in 1999. And this strong hygienic-ethic is upheld everywhere from parks and rivers, to public restrooms (even those in convenience stores and subway stations).

for the most part, are free of debris, criminals, and even homeless people. “The streets here are so clean that you can eat off the ground!” is how one American singer who lived in Shizuoka told me back in 1999. And this strong hygienic-ethic is upheld everywhere from parks and rivers, to public restrooms (even those in convenience stores and subway stations). In addition, for people sporting a melanin-rich hue like mine, it is reassuring to know that racial-profiling by police doesn’t come close to comparing with the U.S. or U.K. More importantly, even if I am stopped by five-oh, I’m not fearful of being attacked or killed when I reach for my I.D. or driver’s license.

In addition, for people sporting a melanin-rich hue like mine, it is reassuring to know that racial-profiling by police doesn’t come close to comparing with the U.S. or U.K. More importantly, even if I am stopped by five-oh, I’m not fearful of being attacked or killed when I reach for my I.D. or driver’s license.

For years, I was lulled to sleep by my sanitary, shiny surroundings and the quiet, incident-free train rides to and from work. Then, one day, on my normal Osaka – Kyoto commute on the Keihan Railway (which has to be the slowest train in Japan), just as I was drifting off to sleep, an ‘a-ha moment’ hit me so hard I was suddenly jarred wide-awake. Removing my headphones, I noticed that aside from the public announcements and the jolting movements of the train as we glided down the tracks, like always, there was barely any noise at all. Japanese are reserved by nature—okay I get that—but on such a crowded train during rush hour it was too quiet. And like I said, it was always too damn quiet! I now realized that what I initially mistook for peace and tranquility was actually more comparable to the imposed silence and depression in a concentration camp. To confirm my theory, I glanced around at some of the other passengers from my seat—even though I knew this was taboo.  As soon as I committed this social gaffe everyone, it seemed, turned in my direction and trained their eyes on me. Although they only stared, I could’ve sworn they were at least pointing, if not spitting and hurling insults—this is how much I felt their resentment. Suddenly, the incessantly repeating announcements instructing passengers to be quiet, and to put their cell-phones on manner-mode so as to “not bother anyone nearby,” sounded louder than ever. Feeling claustrophobic, I stood up and grabbed my bag before navigating through the crowd toward the exit of the still-moving train. Although I did not feel physically threatened, I was now painfully aware of the severe level of anxiety around me. It felt like I was suffocating so I just wanted to change locations. After finding a vacant area near the door, I leaned back, took a deep breath, and just stared out the window as blurred images of houses, parking lots, and pachinko parlors whizzed by.

As soon as I committed this social gaffe everyone, it seemed, turned in my direction and trained their eyes on me. Although they only stared, I could’ve sworn they were at least pointing, if not spitting and hurling insults—this is how much I felt their resentment. Suddenly, the incessantly repeating announcements instructing passengers to be quiet, and to put their cell-phones on manner-mode so as to “not bother anyone nearby,” sounded louder than ever. Feeling claustrophobic, I stood up and grabbed my bag before navigating through the crowd toward the exit of the still-moving train. Although I did not feel physically threatened, I was now painfully aware of the severe level of anxiety around me. It felt like I was suffocating so I just wanted to change locations. After finding a vacant area near the door, I leaned back, took a deep breath, and just stared out the window as blurred images of houses, parking lots, and pachinko parlors whizzed by.

From that day onward I’ve been keenly aware of an intangible cloud of depression, despair, and loneliness that hovers over Japan.  Unlike in the Americas, where life’s challenges are so tangible and direct they might slap you in the face (i.e. police brutality or getting mugged), Japan is a world of illusion: nothing is ever what it appears to be. Many issues that seem insignificant due to their passive, kawaii packaging may be, in reality, as constant and never-ending as the “Chinese Water Torture.” For example, Japanese are inundated with simple obligations such as exchanging winter-holiday greetings called Nenkajo (年賀状), or buying Omiyage (お土産), which are souvenirs for friends and co-workers while on a trip. From these descriptions, both customs seem like nothing more than amicable gestures. That is until one realizes they are obligatory—not optional. And furthermore, there are several times a year when etiquette dictates the exchange of gifts—not just on New Years and the occasional business trip. Again, it cannot be emphasized enough how Japanese constantly feel pressure to fulfill a plethora of responsibilities. To do otherwise would be to lose face. And since these duties to their family, company, school, or even town are persistent and without end, over a period of time, they have a tendency to wear down even the strongest wills.

Unlike in the Americas, where life’s challenges are so tangible and direct they might slap you in the face (i.e. police brutality or getting mugged), Japan is a world of illusion: nothing is ever what it appears to be. Many issues that seem insignificant due to their passive, kawaii packaging may be, in reality, as constant and never-ending as the “Chinese Water Torture.” For example, Japanese are inundated with simple obligations such as exchanging winter-holiday greetings called Nenkajo (年賀状), or buying Omiyage (お土産), which are souvenirs for friends and co-workers while on a trip. From these descriptions, both customs seem like nothing more than amicable gestures. That is until one realizes they are obligatory—not optional. And furthermore, there are several times a year when etiquette dictates the exchange of gifts—not just on New Years and the occasional business trip. Again, it cannot be emphasized enough how Japanese constantly feel pressure to fulfill a plethora of responsibilities. To do otherwise would be to lose face. And since these duties to their family, company, school, or even town are persistent and without end, over a period of time, they have a tendency to wear down even the strongest wills.

Daily Life = Stress Overload

Over the years, some of my private English lessons have gradually morphed into something closer to psychotherapy consultations. I imagine these counseling sessions, which have been occurring more frequently as of late, have less to do with my experience as a social worker and more about the fact that most Japanese don’t feel comfortable enough to discuss (Japanese) issues with either people who they believe know nothing about their culture, i.e. foreigners, or those who are fully-integrated into their society, i.e. a born-and-bred Japanese. It seems I am regarded as being somewhere in the middle. One of these students, a married woman in her late-30s, told me that whenever her husband goes on business trips she is required to spend a couple hours each day with her mother-in-law. Although it is done under the pretext of helping her husband’s mother with cooking, cleaning, shopping, etc., the woman told me she knows it’s just an excuse for the mother-in-law to be nosy and to keep an eye on her. While it’s true that over-bearing mother-in-laws are not unique to Japan, I’ve never heard of them (across the board) wielding so much power. In addition, the same lady oftentimes complains about the numerous Shinto or Buddhist rites that fall on certain days which, in addition to a financial contribution, also require a visit to a consecrated place like a shrine or temple. To be honest, for over a year, I wrote her off as nothing more than a whiner, especially when one of her distant relatives died and she was moaning about the Buddhist ceremonies called Shonanoka (初七日) and Shijūkunichi (四十九日), which are rituals held on the 7th and the 49th day after the death. But then, I began to reflect on how any extra obligations she incurs are in addition to her 8-hour work day as an OL (Office Lady); and since her husband has a 10 – 14 hour work-day—plus mandatory drinking parties after-work—it is just as hectic for him too. ![—cŽ™‚Qlæ‚é“d“®Ž©“]ŽÔ](https://takuanamaru.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/mom-and-kids-on-bike.jpg) Although women normally have a shorter work-day and fewer after-work responsibilities than men, this is only because it is understood they have housewife duties waiting at home which include picking-up and rearing the children all by herself. In Nippon Series 9, we examined some of the consequences of surviving in such a stressful environment such as karoshi (death from overwork), jisatsu (suicide), and hikikomori (vagabond hermitage); so in this edition we shall examine a few of the unique and—I might as well just say it—weird ways Japanese choose to combat their own feelings of isolation and stress.

Although women normally have a shorter work-day and fewer after-work responsibilities than men, this is only because it is understood they have housewife duties waiting at home which include picking-up and rearing the children all by herself. In Nippon Series 9, we examined some of the consequences of surviving in such a stressful environment such as karoshi (death from overwork), jisatsu (suicide), and hikikomori (vagabond hermitage); so in this edition we shall examine a few of the unique and—I might as well just say it—weird ways Japanese choose to combat their own feelings of isolation and stress.

Rent-A-Family (レンタル家族)

It’s extremely strange to me that people would want to rent families, and even more surprising that they seem to be satisfied

~Dr. Takeshi Sato, Sociology professor, Hitotsubashi University.

A Rental Family Service or Professional Stand-In Service sends actors to spend time with their clients. Normally, the actors go the client’s home; but occasionally they attend social events such as weddings or other public ceremonies. Since the actors portray the client’s family members, friends, or coworkers, this allows the client to exist in a temporary, superficial world of illusion where they have positive relationships and are the center of attention. “I suppose people nowadays really find the need for kinship.  Compared to 50 years ago, the family system in Japan has really changed, and family-like relationships are gradually disappearing,” commented Dr. Sato in an attempt to explain this phenomenon. Since these services started popping up during the early 1990s, by now, many people have gotten used to them. For this reason, it seems, Japan felt the need to move the “strangeness bar” up a notch higher; and low and behold, they did it with their newly introduced, “Do-Nothing Services.” Called 「レンタルなんもしない人」 or just 「何もしないを職業」 in Japanese, these agencies send people to clients just like the rental-family-services; however unlike the previously mentioned establishments, these employees are paid to do nothing except show up—that’s right absolutely nothing. They literally just stand next to, or sit with, the client and do nothing except provide quiet company; they don’t even talk! How lonely does a person have to be before they start contemplating on hiring a complete stranger to accompany them to the mall? Or sit across from them (quietly) in a coffee shop? For those who have never lived here, it’s almost impossible to understand to the degree in which Japanese have been indoctrinated with a “group-only” mentality. Put another way, an individual has very little value in this society; his/her worth is equivalent to the reputation of their family, school, company, or other affiliation.

Compared to 50 years ago, the family system in Japan has really changed, and family-like relationships are gradually disappearing,” commented Dr. Sato in an attempt to explain this phenomenon. Since these services started popping up during the early 1990s, by now, many people have gotten used to them. For this reason, it seems, Japan felt the need to move the “strangeness bar” up a notch higher; and low and behold, they did it with their newly introduced, “Do-Nothing Services.” Called 「レンタルなんもしない人」 or just 「何もしないを職業」 in Japanese, these agencies send people to clients just like the rental-family-services; however unlike the previously mentioned establishments, these employees are paid to do nothing except show up—that’s right absolutely nothing. They literally just stand next to, or sit with, the client and do nothing except provide quiet company; they don’t even talk! How lonely does a person have to be before they start contemplating on hiring a complete stranger to accompany them to the mall? Or sit across from them (quietly) in a coffee shop? For those who have never lived here, it’s almost impossible to understand to the degree in which Japanese have been indoctrinated with a “group-only” mentality. Put another way, an individual has very little value in this society; his/her worth is equivalent to the reputation of their family, school, company, or other affiliation.

Some stress-release systems which are not so odd but may only have a real foothold in Japan are Host/Hostess Clubs, Kyabakura 「キャバクラ」, “Snack” 「スナック」 bars, and the newly popular Aiseki-izakayas 「相席居酒屋 」. All of these are varying levels (as far as price and quality) of lounges where clients pay to be catered to by the opposite sex. Established in the late 1960s, even before the Economic “Bubble” (in the 80s) this type of entertainment had already become a staple of Tokyo nightlife. Everyone I spoke with agreed that nowadays these clubs are so widespread they are considered a custom or tradition among Sararimen. If you are interested in further details there is so much information available on the first three clubs, but not so much on the newest kid on the block. Aiseki-izakayas are pubs where people who are seeking a romantic partner are paired with a complete stranger of the opposite sex. Over simple dishes and alcoholic beverages, the two talk and get to know each other.

Evidently there is a fortune to be made by capitalizing on the loneliness and isolation that many Japanese feel. For a nation obsessed with group ethics, Japanese pay top-dollar to escape the rigid parameters they impose on themselves and each other. This feeling of being trapped, in many cases, leads to forms of entertainment which satisfy the lower, more base (and oftentimes concealed) desires—especially in the sex industry.

Cuddle Cafes

The first Cuddle Cafes opened in Tokyo in 2012. Called Soine-ya 「ソイネ屋」, which in Japanese literally means “sleep-together shop,” these venues provide male customers the opportunity to sleep next to a beautiful woman for a fee. According to one article I found about shops in Akihabara, Tokyo, prices range from a 20-minute nap for ¥3,000 ($38 USD) to a 10-hour full-night-sleep package for ¥50,000 ($640 USD).  However, there are options as well. If you want to choose which girl you want to sleep with, it is an additional ¥1,000 plus another ¥500 for each hour. Moreover, if you want to sleep on the girl’s lap, that’s another ¥1,000; and if you want her to sleep on your lap, the price doubles to ¥2,000. Although the sites I perused emphatically state there is no sexual activity occurring, when you look at some of the available choices such as stroking the girl’s hair, staring in each other’s eyes for 1 minute, or giving/receiving special types of caressing—plus the women are attired in panties and sexy nightgowns—it is beyond my understanding how this does not lead to intercourse.

However, there are options as well. If you want to choose which girl you want to sleep with, it is an additional ¥1,000 plus another ¥500 for each hour. Moreover, if you want to sleep on the girl’s lap, that’s another ¥1,000; and if you want her to sleep on your lap, the price doubles to ¥2,000. Although the sites I perused emphatically state there is no sexual activity occurring, when you look at some of the available choices such as stroking the girl’s hair, staring in each other’s eyes for 1 minute, or giving/receiving special types of caressing—plus the women are attired in panties and sexy nightgowns—it is beyond my understanding how this does not lead to intercourse.

Creepy or curious – you decide. It’s undoubtedly weird, however.

~Nicci Martel

Hentai Comics

From a young age, I was exposed to Shunga art from the Japanese magazines lying around our house; so I knew that compared to Caucasians, Japanese had a much more liberal perspective on sex and the (naked) human body.  That said, the porn industry in Japan is a dark, vast, bottomless pit which goes deeper than the average person can imagine—way down into a diabolical, hellish realm which can only be described with adjectives like obscene, ghoulish, or even macabre. For this reason, we are only going to skim the surface of this topic. By now (from the Internet), we should all be aware that what may be considered nasty, lewd, or indecent to some is sure to be described by others as suggestive, seductive…even erotic. The word Hentai is composed of two a kanji characters: 「変」 , meaning weird, and 「態」, meaning appearance or condition, i.e. perversion. Although perverts are not limited to Japan, many of the images in these comics / anime are rarely, if ever, seen in western erotica. While Japanese (Tatamae) identifies Hentai Comics as “strange,” the real deal (Honne) is sexploitation thrives here like nowhere else in the world. Here are a few of the more popular fetishes from a very long list.

That said, the porn industry in Japan is a dark, vast, bottomless pit which goes deeper than the average person can imagine—way down into a diabolical, hellish realm which can only be described with adjectives like obscene, ghoulish, or even macabre. For this reason, we are only going to skim the surface of this topic. By now (from the Internet), we should all be aware that what may be considered nasty, lewd, or indecent to some is sure to be described by others as suggestive, seductive…even erotic. The word Hentai is composed of two a kanji characters: 「変」 , meaning weird, and 「態」, meaning appearance or condition, i.e. perversion. Although perverts are not limited to Japan, many of the images in these comics / anime are rarely, if ever, seen in western erotica. While Japanese (Tatamae) identifies Hentai Comics as “strange,” the real deal (Honne) is sexploitation thrives here like nowhere else in the world. Here are a few of the more popular fetishes from a very long list.

- Shibari 「縛り」 is a Japanese word that literally means “to tie decoratively.” It is a Japanese form of BDSM (bondage, discipline, dominance and submission) using ropes. Basically, it is a form of sadomasochism.

- Bukkake 「ぶっかけ」 is the act of having sex in which one participant is ejaculated on by two or more other participants. Although this, in and of itself, is not so strange by western standards, for it to be so popular in comics is bizarre.

- Gokkun「ゴックン」 is sexual activity in which a person consumes the semen of multiple men, usually from some kind of container.

- Omorashi 「おもらし / オモラシ / お漏らし」 is arousal from wetting yourself; or watching someone else do so.

- Shokushu Goukan 「触手強姦」 Since the translation of this is “Tentacle Violation,” “Tentacle Erotica” or “Tentacle Rape,” I’ll let you use your imagination for a description; nevertheless one question needs to be asked: what’s up with Japanese and octopus?

As I mentioned before, thank God my friends had not known about Hentai Comics back when they were making fun of that octopus in my freezer!

Conclusion

Becoming aware of the skyrocketing levels of stress and anguish lead to understanding why Japanese are so desperate for human contact.  There’s a saying: “Everything is okay in moderation.” However the strict, unforgiving rules in their world provide neither the time nor the luxury for sober self-restraint. This is because what is demanded of Japanese on daily basis almost forces them, in their few moments of free-time, to seek extreme methods to release their frustration. And it’s this type of desperation which sows the seeds for the weird sexual fetishes and other pathological behaviors which abound in Japan. It is also worth noting there is a large amount of research to substantiate the idea that problematic pornography use correlates with psychological problems such as depression and anxiety. I am not here to impose moral judgment on what is, or isn’t, an appropriate form of recreation but, rather, to direct attention to both the source and the consequences of the issue at hand. Recently, at a “Me Too” rally in Tokyo, a woman named Ms. Wakana Goto perfectly expressed my point: “In Japan, with its reputation as one of the world’s safest countries, I have been exposed to sexual harassment since the age of three, forced to get used to it, and to learn to deal with it.”

There’s a saying: “Everything is okay in moderation.” However the strict, unforgiving rules in their world provide neither the time nor the luxury for sober self-restraint. This is because what is demanded of Japanese on daily basis almost forces them, in their few moments of free-time, to seek extreme methods to release their frustration. And it’s this type of desperation which sows the seeds for the weird sexual fetishes and other pathological behaviors which abound in Japan. It is also worth noting there is a large amount of research to substantiate the idea that problematic pornography use correlates with psychological problems such as depression and anxiety. I am not here to impose moral judgment on what is, or isn’t, an appropriate form of recreation but, rather, to direct attention to both the source and the consequences of the issue at hand. Recently, at a “Me Too” rally in Tokyo, a woman named Ms. Wakana Goto perfectly expressed my point: “In Japan, with its reputation as one of the world’s safest countries, I have been exposed to sexual harassment since the age of three, forced to get used to it, and to learn to deal with it.”

Takuan Amaru is the author of Gaikokujin-the Story.