Of religions there are several kinds – Buddhism, Christianity, and what not. From my standpoint there is no more difference between those than between green tea and black…

~Fukuzawa Yukichi, founder of Keio University ~ —

Contrary to popular belief Japan has an official religion; but it is neither Shinto nor Buddhism. While both are widespread, according to nationwide surveys, the overwhelming majority of Japanese do not identify exclusively with either spiritual system. In fact, it has become commonplace for an infant, at birth, to be blessed at a Shinto shrine, as an adult, to get married at a church, and at the time of death, be laid to rest at a Buddhist temple. And what about Christianity?  Although it’s not uncommon to see churches nowadays, the “Land of the Rising Sun” is one of the few industrialized nations where the Abrahamic doctrines did not really catch on; so very few people identify as Jewish, Muslim, or Christian. In countries where both exist, Eastern spiritual systems usually get overshadowed by western denominations. But not in Japan. Although Jesuit priests like Francis Xavier started arriving in Kyushu as far back as the mid-1500s, Japan never fully-adopted any of the western religions like other (colonized) countries in Asia and Africa. As a result, Japanese were never indoctrinated with the concept of God/Goddess being a white man. Could this be why Japanese, during the 20th century, were unafraid to wage war against the Western world—not once but twice?

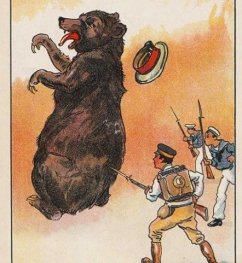

Although it’s not uncommon to see churches nowadays, the “Land of the Rising Sun” is one of the few industrialized nations where the Abrahamic doctrines did not really catch on; so very few people identify as Jewish, Muslim, or Christian. In countries where both exist, Eastern spiritual systems usually get overshadowed by western denominations. But not in Japan. Although Jesuit priests like Francis Xavier started arriving in Kyushu as far back as the mid-1500s, Japan never fully-adopted any of the western religions like other (colonized) countries in Asia and Africa. As a result, Japanese were never indoctrinated with the concept of God/Goddess being a white man. Could this be why Japanese, during the 20th century, were unafraid to wage war against the Western world—not once but twice?  While everyone recalls Japan’s tragic surrender in 1945, following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, most forget the stinging defeat they handed Russia at the turn of the century. More than a few noted scholars of the time, including W.E.B. Dubois, saw this victory as a legitimate challenge to western supremacy. Even today, when you consider that Japanese are on a short list of ethnic groups who don’t automatically see Europeans as superior, it appears that Dubois’ line of thinking still holds weight. In the final analysis, no matter how much Japanese teens may fetishize blonde hair, blue eyes, or pale skin, there exists just beneath their consciousness—in their collective subconscious—the understanding that white people are gaijin. No, through all the struggles, triumphs and defeats, the Yamato clan has been able to maintain its national identity.

While everyone recalls Japan’s tragic surrender in 1945, following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, most forget the stinging defeat they handed Russia at the turn of the century. More than a few noted scholars of the time, including W.E.B. Dubois, saw this victory as a legitimate challenge to western supremacy. Even today, when you consider that Japanese are on a short list of ethnic groups who don’t automatically see Europeans as superior, it appears that Dubois’ line of thinking still holds weight. In the final analysis, no matter how much Japanese teens may fetishize blonde hair, blue eyes, or pale skin, there exists just beneath their consciousness—in their collective subconscious—the understanding that white people are gaijin. No, through all the struggles, triumphs and defeats, the Yamato clan has been able to maintain its national identity.

Spirituality vs. Religion

Considering that nowadays every other person you meet claims to be “spiritual but not religious,” this lends itself to the idea that, although the terms share something in common, they are not identical. While the former is an individual endeavor which deals directly with, and calls on, spirits;  the latter is a group-oriented activity which is grounded in a common creed. Scholars such as Jun’ichi Isomae and Jason Ānanda Josephson have argued the concept of “religion” is an invention of the 19th century. This would explain why the Japanese term for it, Shūkyō (宗教), only refers to organized, belief systems. In the West, the etymology of religion is associated with the Latin word religare, which means “to tie,” or, “to bind.” Just as Arabs are connected by Islam, and Jews are bound together by Judaism, Japanese are irrevocably linked by their religion too. As mentioned above, concerning their worship practices, Japanese favor a somewhat syncretic view. Therefore, in spite of the number of shrines and temples dotting the island-nation, which may hint that either Shinto or Buddhism is the main religion, it is difficult to get Japanese to claim either and, of the twenty or so people I asked, none would readily accept being identified as Shintoist or Buddhist. Most people, either directly or indirectly, referenced a concept known as Shinbutsu-Shūgō (神仏習合), which is a syncretism of Kami and Buddhas.

the latter is a group-oriented activity which is grounded in a common creed. Scholars such as Jun’ichi Isomae and Jason Ānanda Josephson have argued the concept of “religion” is an invention of the 19th century. This would explain why the Japanese term for it, Shūkyō (宗教), only refers to organized, belief systems. In the West, the etymology of religion is associated with the Latin word religare, which means “to tie,” or, “to bind.” Just as Arabs are connected by Islam, and Jews are bound together by Judaism, Japanese are irrevocably linked by their religion too. As mentioned above, concerning their worship practices, Japanese favor a somewhat syncretic view. Therefore, in spite of the number of shrines and temples dotting the island-nation, which may hint that either Shinto or Buddhism is the main religion, it is difficult to get Japanese to claim either and, of the twenty or so people I asked, none would readily accept being identified as Shintoist or Buddhist. Most people, either directly or indirectly, referenced a concept known as Shinbutsu-Shūgō (神仏習合), which is a syncretism of Kami and Buddhas.  The fusing of Shinto and Buddhism was especially popular during the Heian Era (794-1185), suggesting that this blending of spiritual principles is nothing new. Unlike the Judeo-Christian societies, which have always forced their dogma onto the common people at the edge of a sword, Japanese have never endorsed inflicting physical violence against “nonbelievers who lack faith.” Although there were eras when people were required to register at either a shrine or a temple, these mandates never led to any “inquisitions.” Many prominent scholars, including Rev. William Elliott Griffis and Nobuto Kishimoto, teach that in addition to Shinto and Buddhism there is a third pillar of Japanese religion: Confucianism. According to Kishimoto: “Shintoism furnishes the object, Confucianism offers the rules of life, while Buddhism supplies the way of salvation.”

The fusing of Shinto and Buddhism was especially popular during the Heian Era (794-1185), suggesting that this blending of spiritual principles is nothing new. Unlike the Judeo-Christian societies, which have always forced their dogma onto the common people at the edge of a sword, Japanese have never endorsed inflicting physical violence against “nonbelievers who lack faith.” Although there were eras when people were required to register at either a shrine or a temple, these mandates never led to any “inquisitions.” Many prominent scholars, including Rev. William Elliott Griffis and Nobuto Kishimoto, teach that in addition to Shinto and Buddhism there is a third pillar of Japanese religion: Confucianism. According to Kishimoto: “Shintoism furnishes the object, Confucianism offers the rules of life, while Buddhism supplies the way of salvation.”

Administration of Shame

At the beginning of the 17th century, the Tokugawa Shogunate, obsessed with crushing any threat to its authority, encouraged Confucianism due to its focus on morality and ethics. One of the creeds which served this end well came from a 12th century Confucian scholar, Chu Hsi (朱熹), due to his belief in unwavering loyalty and duty to one’s parents…and rulers. Today, aspects of this teaching are still evident in the steadfast devotion Japanese have for their school, company, or just society in general. Jonathon Rice, author of Behind the Japanese Mask, calls Confucianism “the moral underpinning of the Japanese way of life.” Nevertheless the question one must ask is: How is this unfailing dedication to the values of society so thoroughly programmed into each and every person? According to Master Kǒng himself, otherwise known as “Confucius” (孔夫子), the solution lies in creating an atmosphere where the slightest deviance from normalcy leads to a personal sense of shame:

If you control people by punishment, they will avoid crime, but have no personal sense of shame. If you govern by means of virtue and control them with propriety, they will gain their own sense of shame and thus correct themselves

~The Analects

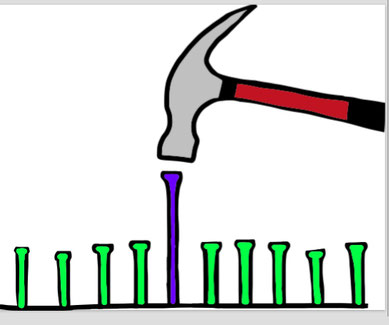

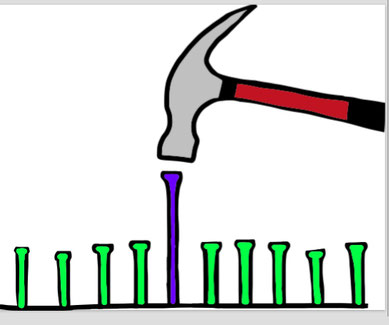

Wa (和), a cultural concept meaning “harmony,” implies peaceful relations among members of a social group but, in reality, it is far from tranquil. Considered integral to Japanese society, individuals who dare to “go against the grain” are reprimanded by a tidal wave of disapproval by superiors, family members, and colleagues via methods which might be hard for westerners to imagine. This is simply because, in many cases, words are never exchanged.  “The nail that sticks out gets hammered down” (出る釘は打たれる) is the famous adage which best expresses the immense societal pressure placed on Japanese to conform. In such a homogenous-thinking society, unless you’re a politician or an entertainer, standing out from the crowd is not only frowned upon, it results in being marginalized to a state of communal purgatory. Ian Buruma, who is the author of a number of books on Japan, stated: “Social rules, rather than an abstract system of morals, control Japanese behaviour.” It took several years of working in Japanese schools, both public and private, before I realized the priority of the faculty was not formal education but, rather, to teach the children to “be Japanese,” i.e. show them their place within the societal framework. With an average of 38 students in each homeroom, since students do not change classes for each subject (except Phys Ed and labs), they stay-put in the same, overcrowded classroom—including lunch—for 8 – 10 hours. It is here, through constant trial, trauma, and tribulation, the collective subconscious is programmed with the idea that “we” in this classroom must struggle together (Ganbare!), along with the unspoken truth that accompanies such reasoning: all those outside “our world” are insignificant. Concurrent with the nurturing of this “Us only” mentality is the Confucian teaching to respect authority. For young people, they learn their role, for the time being, is to sit down, be quiet, and follow orders—which brings us back to the edict of teachers “showing them their place.” Put another way, while there are lessons on math, science, and history being taught, the goal of the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (文部科学省), also known as MEXT, is not to raise test scores or elevate student’s intellect so much as it is to put every youth on-code. The Japanese Code. This is the true religion. And just like Marine boot-camp or any training program designed to get people on the “same page,” not only is it necessary to eradicate critical-thinking but, in addition, to cancel any notion of independence or existing apart from the group. With virtually all of the actual teaching and learning of academic subjects occurring in the evening at cram-schools called Juku (塾), this allows schools to operate along strict guidelines which bear a closer resemblance to military training than formal education.

“The nail that sticks out gets hammered down” (出る釘は打たれる) is the famous adage which best expresses the immense societal pressure placed on Japanese to conform. In such a homogenous-thinking society, unless you’re a politician or an entertainer, standing out from the crowd is not only frowned upon, it results in being marginalized to a state of communal purgatory. Ian Buruma, who is the author of a number of books on Japan, stated: “Social rules, rather than an abstract system of morals, control Japanese behaviour.” It took several years of working in Japanese schools, both public and private, before I realized the priority of the faculty was not formal education but, rather, to teach the children to “be Japanese,” i.e. show them their place within the societal framework. With an average of 38 students in each homeroom, since students do not change classes for each subject (except Phys Ed and labs), they stay-put in the same, overcrowded classroom—including lunch—for 8 – 10 hours. It is here, through constant trial, trauma, and tribulation, the collective subconscious is programmed with the idea that “we” in this classroom must struggle together (Ganbare!), along with the unspoken truth that accompanies such reasoning: all those outside “our world” are insignificant. Concurrent with the nurturing of this “Us only” mentality is the Confucian teaching to respect authority. For young people, they learn their role, for the time being, is to sit down, be quiet, and follow orders—which brings us back to the edict of teachers “showing them their place.” Put another way, while there are lessons on math, science, and history being taught, the goal of the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (文部科学省), also known as MEXT, is not to raise test scores or elevate student’s intellect so much as it is to put every youth on-code. The Japanese Code. This is the true religion. And just like Marine boot-camp or any training program designed to get people on the “same page,” not only is it necessary to eradicate critical-thinking but, in addition, to cancel any notion of independence or existing apart from the group. With virtually all of the actual teaching and learning of academic subjects occurring in the evening at cram-schools called Juku (塾), this allows schools to operate along strict guidelines which bear a closer resemblance to military training than formal education.

Social Totalitarianism: To be or not to be Japanese

Totalitarianism is a political system that prohibits any opposition whatsoever to the government. Regarded as a form of authoritarianism, it exercises an extremely high degree of control over public and private affairs. Mao Zedong, former Chairman of the Communist Party in China, Joseph Stalin, former leader of the Soviet Union, along with Adolf Hitler, led prototypical totalitarian regimes. In contrast to these dictatorships, the programming and the pressure to “be Japanese” is not coming from the government per se but, instead, is being imposed on the people—by the people themselves. Each Japanese heart yearns to beat in accordance with the drumbeat of society: this is the Yamato spirit. For this reason, instead of Shinto, Buddhism, or Confucianism, perhaps it would be more appropriate to call the Japanese religion something with “Yamato” in it. Or, we can simply call it Tatamae which, after all, is the embodiment of social totalitarianism because anyone who does not comply with the “Japanese programming” is subject to the societal thought-police who regulate through a special type of bullying called Ijime (イジメ, 虐め). A former colleague of mine, Watanabe-sensei, explained that “Ijime is as much a part of Japanese culture as sukiyaki, sumo wrestling, or green tea.” So accordingly, when Shinnosuke Komatsuda, a 15-year-old boy from Saitama Prefecture, committed suicide in September due to being the target of bullying at school, even though it is no secret as to what took place, no one was surprised to hear the boy’s mother blame the school and ask for a full investigation. Why? Because it’s in the script; this is what grieving parents of bullied victims always say on the news. What else could she do? Admit she had failed to teach her son the values of society? No. She, along with everyone else, knows her son either could not, or would not, adjust to the standard that had been set by the members of the homeroom—his society—and therefore he was sacrificed to the game. At that point, her only concern was to be granted a reprieve. Not only was she grieving the death of her son, she was being singled-out (which we’ve already defined as communal purgatory); so in order to “save face” she had to say what was expected of her. The essay entitled Shame, Honor, and Duty really drives this point home:

No. She, along with everyone else, knows her son either could not, or would not, adjust to the standard that had been set by the members of the homeroom—his society—and therefore he was sacrificed to the game. At that point, her only concern was to be granted a reprieve. Not only was she grieving the death of her son, she was being singled-out (which we’ve already defined as communal purgatory); so in order to “save face” she had to say what was expected of her. The essay entitled Shame, Honor, and Duty really drives this point home:

Why does shame have to be avoided at all costs? In Japan, relationships between people are greatly affected by duty and obligation. In duty-based relationships, what other people believe or think has a more powerful impact on behavior than what the individual believes. Shame occurs through others’ negative feelings towards you or through your feelings of having failed to live up to your obligations…but in Japanese culture, shame cannot be removed until a person does what society expects

~Takako McCrann, Ph.D.

Takuan Amaru is the author of Gaikokujin – The Story

Takuan Amaru

Of religions there are several kinds – Buddhism, Christianity, and what not. From my standpoint there is no more difference between those than between green tea and black…

~Fukuzawa Yukichi, founder of Keio University ~ —

Contrary to popular belief Japan has an official religion; but it is neither Shinto nor Buddhism. While both are widespread, according to nationwide surveys, the overwhelming majority of Japanese do not identify exclusively with either spiritual system. In fact, it has become commonplace for an infant, at birth, to be blessed at a Shinto shrine, as an adult, to get married at a church, and at the time of death, be laid to rest at a Buddhist temple. And what about Christianity?  Although it’s not uncommon to see churches nowadays, the “Land of the Rising Sun” is one of the few industrialized nations where the Abrahamic doctrines did not really catch on; so very few people identify as Jewish, Muslim, or Christian. In countries where both exist, Eastern spiritual systems usually get overshadowed by western denominations. But not in Japan. Although Jesuit priests like Francis Xavier started arriving in Kyushu as far back as the mid-1500s, Japan never fully-adopted any of the western religions like other (colonized) countries in Asia and Africa. As a result, Japanese were never indoctrinated with the concept of God/Goddess being a white man. Could this be why Japanese, during the 20th century, were unafraid to wage war against the Western world—not once but twice?

Although it’s not uncommon to see churches nowadays, the “Land of the Rising Sun” is one of the few industrialized nations where the Abrahamic doctrines did not really catch on; so very few people identify as Jewish, Muslim, or Christian. In countries where both exist, Eastern spiritual systems usually get overshadowed by western denominations. But not in Japan. Although Jesuit priests like Francis Xavier started arriving in Kyushu as far back as the mid-1500s, Japan never fully-adopted any of the western religions like other (colonized) countries in Asia and Africa. As a result, Japanese were never indoctrinated with the concept of God/Goddess being a white man. Could this be why Japanese, during the 20th century, were unafraid to wage war against the Western world—not once but twice?  While everyone recalls Japan’s tragic surrender in 1945, following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, most forget the stinging defeat they handed Russia at the turn of the century. More than a few noted scholars of the time, including W.E.B. Dubois, saw this victory as a legitimate challenge to western supremacy. Even today, when you consider that Japanese are on a short list of ethnic groups who don’t automatically see Europeans as superior, it appears that Dubois’ line of thinking still holds weight. In the final analysis, no matter how much Japanese teens may fetishize blonde hair, blue eyes, or pale skin, there exists just beneath their consciousness—in their collective subconscious—the understanding that white people are gaijin. No, through all the struggles, triumphs and defeats, the Yamato clan has been able to maintain its national identity.

While everyone recalls Japan’s tragic surrender in 1945, following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, most forget the stinging defeat they handed Russia at the turn of the century. More than a few noted scholars of the time, including W.E.B. Dubois, saw this victory as a legitimate challenge to western supremacy. Even today, when you consider that Japanese are on a short list of ethnic groups who don’t automatically see Europeans as superior, it appears that Dubois’ line of thinking still holds weight. In the final analysis, no matter how much Japanese teens may fetishize blonde hair, blue eyes, or pale skin, there exists just beneath their consciousness—in their collective subconscious—the understanding that white people are gaijin. No, through all the struggles, triumphs and defeats, the Yamato clan has been able to maintain its national identity.

Spirituality vs. Religion

Considering that nowadays every other person you meet claims to be “spiritual but not religious,” this lends itself to the idea that, although the terms share something in common, they are not identical. While the former is an individual endeavor which deals directly with, and calls on, spirits;  the latter is a group-oriented activity which is grounded in a common creed. Scholars such as Jun’ichi Isomae and Jason Ānanda Josephson have argued the concept of “religion” is an invention of the 19th century. This would explain why the Japanese term for it, Shūkyō (宗教), only refers to organized, belief systems. In the West, the etymology of religion is associated with the Latin word religare, which means “to tie,” or, “to bind.” Just as Arabs are connected by Islam, and Jews are bound together by Judaism, Japanese are irrevocably linked by their religion too. As mentioned above, concerning their worship practices, Japanese favor a somewhat syncretic view. Therefore, in spite of the number of shrines and temples dotting the island-nation, which may hint that either Shinto or Buddhism is the main religion, it is difficult to get Japanese to claim either and, of the twenty or so people I asked, none would readily accept being identified as Shintoist or Buddhist. Most people, either directly or indirectly, referenced a concept known as Shinbutsu-Shūgō (神仏習合), which is a syncretism of Kami and Buddhas.

the latter is a group-oriented activity which is grounded in a common creed. Scholars such as Jun’ichi Isomae and Jason Ānanda Josephson have argued the concept of “religion” is an invention of the 19th century. This would explain why the Japanese term for it, Shūkyō (宗教), only refers to organized, belief systems. In the West, the etymology of religion is associated with the Latin word religare, which means “to tie,” or, “to bind.” Just as Arabs are connected by Islam, and Jews are bound together by Judaism, Japanese are irrevocably linked by their religion too. As mentioned above, concerning their worship practices, Japanese favor a somewhat syncretic view. Therefore, in spite of the number of shrines and temples dotting the island-nation, which may hint that either Shinto or Buddhism is the main religion, it is difficult to get Japanese to claim either and, of the twenty or so people I asked, none would readily accept being identified as Shintoist or Buddhist. Most people, either directly or indirectly, referenced a concept known as Shinbutsu-Shūgō (神仏習合), which is a syncretism of Kami and Buddhas.  The fusing of Shinto and Buddhism was especially popular during the Heian Era (794-1185), suggesting that this blending of spiritual principles is nothing new. Unlike the Judeo-Christian societies, which have always forced their dogma onto the common people at the edge of a sword, Japanese have never endorsed inflicting physical violence against “nonbelievers who lack faith.” Although there were eras when people were required to register at either a shrine or a temple, these mandates never led to any “inquisitions.” Many prominent scholars, including Rev. William Elliott Griffis and Nobuto Kishimoto, teach that in addition to Shinto and Buddhism there is a third pillar of Japanese religion: Confucianism. According to Kishimoto: “Shintoism furnishes the object, Confucianism offers the rules of life, while Buddhism supplies the way of salvation.”

The fusing of Shinto and Buddhism was especially popular during the Heian Era (794-1185), suggesting that this blending of spiritual principles is nothing new. Unlike the Judeo-Christian societies, which have always forced their dogma onto the common people at the edge of a sword, Japanese have never endorsed inflicting physical violence against “nonbelievers who lack faith.” Although there were eras when people were required to register at either a shrine or a temple, these mandates never led to any “inquisitions.” Many prominent scholars, including Rev. William Elliott Griffis and Nobuto Kishimoto, teach that in addition to Shinto and Buddhism there is a third pillar of Japanese religion: Confucianism. According to Kishimoto: “Shintoism furnishes the object, Confucianism offers the rules of life, while Buddhism supplies the way of salvation.”

Administration of Shame

At the beginning of the 17th century, the Tokugawa Shogunate, obsessed with crushing any threat to its authority, encouraged Confucianism due to its focus on morality and ethics. One of the creeds which served this end well came from a 12th century Confucian scholar, Chu Hsi (朱熹), due to his belief in unwavering loyalty and duty to one’s parents…and rulers. Today, aspects of this teaching are still evident in the steadfast devotion Japanese have for their school, company, or just society in general. Jonathon Rice, author of Behind the Japanese Mask, calls Confucianism “the moral underpinning of the Japanese way of life.” Nevertheless the question one must ask is: How is this unfailing dedication to the values of society so thoroughly programmed into each and every person? According to Master Kǒng himself, otherwise known as “Confucius” (孔夫子), the solution lies in creating an atmosphere where the slightest deviance from normalcy leads to a personal sense of shame:

If you control people by punishment, they will avoid crime, but have no personal sense of shame. If you govern by means of virtue and control them with propriety, they will gain their own sense of shame and thus correct themselves

~The Analects

Wa (和), a cultural concept meaning “harmony,” implies peaceful relations among members of a social group but, in reality, it is far from tranquil. Considered integral to Japanese society, individuals who dare to “go against the grain” are reprimanded by a tidal wave of disapproval by superiors, family members, and colleagues via methods which might be hard for westerners to imagine. This is simply because, in many cases, words are never exchanged.  “The nail that sticks out gets hammered down” (出る釘は打たれる) is the famous adage which best expresses the immense societal pressure placed on Japanese to conform. In such a homogenous-thinking society, unless you’re a politician or an entertainer, standing out from the crowd is not only frowned upon, it results in being marginalized to a state of communal purgatory. Ian Buruma, who is the author of a number of books on Japan, stated: “Social rules, rather than an abstract system of morals, control Japanese behaviour.” It took several years of working in Japanese schools, both public and private, before I realized the priority of the faculty was not formal education but, rather, to teach the children to “be Japanese,” i.e. show them their place within the societal framework. With an average of 38 students in each homeroom, since students do not change classes for each subject (except Phys Ed and labs), they stay-put in the same, overcrowded classroom—including lunch—for 8 – 10 hours. It is here, through constant trial, trauma, and tribulation, the collective subconscious is programmed with the idea that “we” in this classroom must struggle together (Ganbare!), along with the unspoken truth that accompanies such reasoning: all those outside “our world” are insignificant. Concurrent with the nurturing of this “Us only” mentality is the Confucian teaching to respect authority. For young people, they learn their role, for the time being, is to sit down, be quiet, and follow orders—which brings us back to the edict of teachers “showing them their place.” Put another way, while there are lessons on math, science, and history being taught, the goal of the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (文部科学省), also known as MEXT, is not to raise test scores or elevate student’s intellect so much as it is to put every youth on-code. The Japanese Code. This is the true religion. And just like Marine boot-camp or any training program designed to get people on the “same page,” not only is it necessary to eradicate critical-thinking but, in addition, to cancel any notion of independence or existing apart from the group. With virtually all of the actual teaching and learning of academic subjects occurring in the evening at cram-schools called Juku (塾), this allows schools to operate along strict guidelines which bear a closer resemblance to military training than formal education.

“The nail that sticks out gets hammered down” (出る釘は打たれる) is the famous adage which best expresses the immense societal pressure placed on Japanese to conform. In such a homogenous-thinking society, unless you’re a politician or an entertainer, standing out from the crowd is not only frowned upon, it results in being marginalized to a state of communal purgatory. Ian Buruma, who is the author of a number of books on Japan, stated: “Social rules, rather than an abstract system of morals, control Japanese behaviour.” It took several years of working in Japanese schools, both public and private, before I realized the priority of the faculty was not formal education but, rather, to teach the children to “be Japanese,” i.e. show them their place within the societal framework. With an average of 38 students in each homeroom, since students do not change classes for each subject (except Phys Ed and labs), they stay-put in the same, overcrowded classroom—including lunch—for 8 – 10 hours. It is here, through constant trial, trauma, and tribulation, the collective subconscious is programmed with the idea that “we” in this classroom must struggle together (Ganbare!), along with the unspoken truth that accompanies such reasoning: all those outside “our world” are insignificant. Concurrent with the nurturing of this “Us only” mentality is the Confucian teaching to respect authority. For young people, they learn their role, for the time being, is to sit down, be quiet, and follow orders—which brings us back to the edict of teachers “showing them their place.” Put another way, while there are lessons on math, science, and history being taught, the goal of the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (文部科学省), also known as MEXT, is not to raise test scores or elevate student’s intellect so much as it is to put every youth on-code. The Japanese Code. This is the true religion. And just like Marine boot-camp or any training program designed to get people on the “same page,” not only is it necessary to eradicate critical-thinking but, in addition, to cancel any notion of independence or existing apart from the group. With virtually all of the actual teaching and learning of academic subjects occurring in the evening at cram-schools called Juku (塾), this allows schools to operate along strict guidelines which bear a closer resemblance to military training than formal education.

Social Totalitarianism: To be or not to be Japanese

Totalitarianism is a political system that prohibits any opposition whatsoever to the government. Regarded as a form of authoritarianism, it exercises an extremely high degree of control over public and private affairs. Mao Zedong, former Chairman of the Communist Party in China, Joseph Stalin, former leader of the Soviet Union, along with Adolf Hitler, led prototypical totalitarian regimes. In contrast to these dictatorships, the programming and the pressure to “be Japanese” is not coming from the government per se but, instead, is being imposed on the people—by the people themselves. Each Japanese heart yearns to beat in accordance with the drumbeat of society: this is the Yamato spirit. For this reason, instead of Shinto, Buddhism, or Confucianism, perhaps it would be more appropriate to call the Japanese religion something with “Yamato” in it. Or, we can simply call it Tatamae which, after all, is the embodiment of social totalitarianism because anyone who does not comply with the “Japanese programming” is subject to the societal thought-police who regulate through a special type of bullying called Ijime (イジメ, 虐め). A former colleague of mine, Watanabe-sensei, explained that “Ijime is as much a part of Japanese culture as sukiyaki, sumo wrestling, or green tea.” So accordingly, when Shinnosuke Komatsuda, a 15-year-old boy from Saitama Prefecture, committed suicide in September due to being the target of bullying at school, even though it is no secret as to what took place, no one was surprised to hear the boy’s mother blame the school and ask for a full investigation. Why? Because it’s in the script; this is what grieving parents of bullied victims always say on the news. What else could she do? Admit she had failed to teach her son the values of society? No. She, along with everyone else, knows her son either could not, or would not, adjust to the standard that had been set by the members of the homeroom—his society—and therefore he was sacrificed to the game. At that point, her only concern was to be granted a reprieve. Not only was she grieving the death of her son, she was being singled-out (which we’ve already defined as communal purgatory); so in order to “save face” she had to say what was expected of her. The essay entitled Shame, Honor, and Duty really drives this point home:

No. She, along with everyone else, knows her son either could not, or would not, adjust to the standard that had been set by the members of the homeroom—his society—and therefore he was sacrificed to the game. At that point, her only concern was to be granted a reprieve. Not only was she grieving the death of her son, she was being singled-out (which we’ve already defined as communal purgatory); so in order to “save face” she had to say what was expected of her. The essay entitled Shame, Honor, and Duty really drives this point home:

Why does shame have to be avoided at all costs? In Japan, relationships between people are greatly affected by duty and obligation. In duty-based relationships, what other people believe or think has a more powerful impact on behavior than what the individual believes. Shame occurs through others’ negative feelings towards you or through your feelings of having failed to live up to your obligations…but in Japanese culture, shame cannot be removed until a person does what society expects

~Takako McCrann, Ph.D.

Takuan Amaru is the author of Gaikokujin – The Story