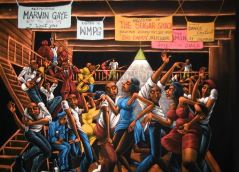

A few weeks ago, I had the pleasure of attending an event hosted by Black Creatives Japan. Black Creatives is a social-media group for independent, progressive-thinking people of Afro-descent. Ms. Ayana Wyse, the organizer of the event, stressed in her promotion that everyone (not only blacks) was welcome; and this is exactly the type of atmosphere we walked into. Upon our arrival, initially, I must admit that I felt a bit perplexed; this is because what I was witnessing both encouraged and alarmed me simultaneously. Although heavily accented with darker hues, the melanin-rich crowd reflected various shades of the human spectrum as brothers and sisters from all parts of the diaspora rubbed shoulders with Japanese as well as the few attending Caucasians.

Laid back and tranquil but friendly, this is hardly the type of “black event” that I was used to attending back in Philly or NYC. Venues where (the threat of) someone getting beat-up, robbed, dissed, or arrested was the normal atmosphere. Well, having to watch my back is easily one of the “black traits” I don’t miss…but on second thought, when I really think about it, the ‘danger’ of attending, let’s say, Hip Hop events in the 90s was part of the allure and excitement.

What I mean is, strange as it may seem, some of the hypest events I’ve been to were likewise (at least potentially) some of the most dangerous. No one ever talked about it but everyone knew that living precariously was a significant part of being black.

Scanning the crowd between acts, it seemed many of the attendees knew little of this type of black experience; so here they were expressing their own version of blackness. I decided to take notes.

My family lived in both Japan and the Philippines before arriving in the U.S. Therefore, as a child, I was often told by black kids: “Tak, you ain’t black!” This was due to my unfamiliar accent and mannerisms; it was not until after puberty that I developed enough swag to be recognized by my brethren. I write it like this because, unlike many other multi-racial people who have bought into the status-quo (i.e. white is right), I immediately intuited blackness as the pinnacle of human existence. Therefore, I’ve always been proud of being Japanese but due to the dominating presence of my father, I’ve always identified as a black man…a black Japanese man.

What is the meaning of “Black?”

By the time my friends and I entered Bar Ludo, which is located in the Shinsaibashi district of Osaka, the Talent Show was already underway. One of the first acts really got my attention. In addition to being attractive, I sensed the caramel-complexioned sista was also (mixed with) Japanese. As a child, whenever I met kids who were like me, we always stared at each other, almost feeling like siblings from another lifetime, or maybe some other parallel world. For me, I was deciphering their identity: basically whether they were choosing to be black or white. Many people claim that nowadays, the black-white dichotomy is being replaced with a class system based more on income brackets than race. Perhaps this is a topic for another article. During the intermission, I approached the young lady and overheard her talking about her racial make-up and the military posts that she had lived on. Having that in common with her, it was easy to strike up a conversation. “I thought you looked like one of us,” she divulged during our discussion. Long before I spoke with her or shook hands with her Caucasian boyfriend, I had already predicted she had not chosen “black. How did I know? Because black females become singers at church and it was clear that she had never sung any gospel music. Just the way she approached the microphone was enough of a tip-off; but when homegirl didn’t know the lyrics to the song, it was a wrap. Leaning forward, I whispered to a sista in front of me who was from Detroit, “You know she didn’t grow up in church.” And together, we shared a snicker.

In addition to being attractive, I sensed the caramel-complexioned sista was also (mixed with) Japanese. As a child, whenever I met kids who were like me, we always stared at each other, almost feeling like siblings from another lifetime, or maybe some other parallel world. For me, I was deciphering their identity: basically whether they were choosing to be black or white. Many people claim that nowadays, the black-white dichotomy is being replaced with a class system based more on income brackets than race. Perhaps this is a topic for another article. During the intermission, I approached the young lady and overheard her talking about her racial make-up and the military posts that she had lived on. Having that in common with her, it was easy to strike up a conversation. “I thought you looked like one of us,” she divulged during our discussion. Long before I spoke with her or shook hands with her Caucasian boyfriend, I had already predicted she had not chosen “black. How did I know? Because black females become singers at church and it was clear that she had never sung any gospel music. Just the way she approached the microphone was enough of a tip-off; but when homegirl didn’t know the lyrics to the song, it was a wrap. Leaning forward, I whispered to a sista in front of me who was from Detroit, “You know she didn’t grow up in church.” And together, we shared a snicker.

Many Japanese are surprised when they learn their favorite American singers honed their craft in a black church.

Under the strict guidance of older black women who, as far as I’m concerned, are the best singing instructors the world has ever known, these teachers squeeze every ounce of musical potential from their on-stage prodigies with a simple but stern, “Sang girl!” (Note: not “sing”) From Aretha Franklin and Whitney Houston to Alicia Keys and Beyonce, the church has been the proving ground for the very best. Perhaps Janet Jackson is the only female singer I can think of, due to being a Jehovah’s Witness, who may not have undergone this indoctrination.

Before I could pat myself on the back for the accuracy of my prediction, another sista with short locs and a dashiki came on-stage. “Oh yeah!” I uttered, believing the show was now getting started. After she announced she was performing a song from the movie, Lion King, I sensed something was amiss. Nonetheless, when she prefaced her act with an apology, I almost screamed out loud: “This is definitely not black!” In hindsight, it would not be fair to critique her because she wasn’t even trying to sing; she was just up there to have fun, kind of like karaoke. What’s more, the crowd supported her through not one, not two, but three songs. Having been schooled on blackness watching shows like Soul Train; or better yet, “Amateur Night” at the Apollo Theater,

where if the performer did not appeal to the audience, she/he got booed harshly before Sandman Sims would tap-dance his way on-stage to sweep the misfits away with his legendary broom—all this amidst catcalls and laughter—I was dumbfounded.

As of late, embracing change has been a challenge. Being a child of the Hip Hop generation, I remember the scorn I felt for “old people” who did not understand our music—especially before there were actual Hip Hop records. No joke, my father would literally become violent if I tried to include anyone in the music category who wasn’t a recognized Jazz Great like Miles Davis, John Coltrane, or Charlie Parker; this even included Smooth Jazz artists like Grover Washington Jr. Back then, I promised myself I’d never become that closed-minded; therefore I want to be careful about how I describe that night’s, hmm, let’s say “fun performances.” That said, near the end of the show, someone did appear who matched my preconceived idea of a singer. Not only were this queen’s lyrics strong and poignant but it seemed she had sung them before (in front of black folks). In addition, being a conscious brother, I especially appreciated her song about ‘melanin magic.’

In conclusion, I’d like to thank Ms. Wyse and her assistants for organizing such a classy event; I met some cool, intelligent, down-to-earth people that night.

Hopefully, she will have another sooner than later, and if I’m fortunate enough to attend who knows, perhaps I’ll try my hand at performing stand-up…especially since everyone’s gonna support me even if I bomb horribly. On second thought, considering there was a comedian there—and the brother held it down—perhaps I’ll just be content to continue taking notes on the ever-changing, evolution of this dynamic called Blackness.”

Takuan Amaru is the author of the trilogy, Gaikokujin – The Story